Mark Twain called the Lion Monument “the most mournful and moving piece of stone in the world.” And while it is not the only moving piece of sculpture I’ve seen, [The Pietà comes to my mind.], the lion’s face conveys unquenchable grief and despair. But for what? The loss of Swiss Guards at the Tuileries Palace in 1792? The fact that the statue’s sponsor Karl Pfyffer von Altishofen was in Lucerne on leave at the time and not with his martial brothers?

Is it the loss of the French Monarchy that was restored in 1815? Is it survivors’ guilt? There is no doubt the monument was meant to honor the fallen Swiss Guards, but it seems as if it should be something more than the remnant of a lost battle.

When his brothers fell in 1792, Pfyffer was not there. When his uncle died in the battle, Pfyffer was safe in Lucerne. French Revolutionaries executed Louis XVI in 1793 while Pfyffer and other surviving Swiss Guards returned to duty fighting for different kings. In 1801, a year before Napoleon made himself First Consul for Life, Pfyffer’s regiment disbanded, and the disillusioned soldier went home to Lucerne.

In honor of his fallen comrades, Pfyffer began to transform his family’s sandstone quarry into an English Garden. He surrounded the remaining cliff face with a pool of water, and began to imagine a monument carved out of the rock.

In 1815 Napoleon suffered his final defeat at the Battle of Waterloo, and the Congress of Vienna redrew the map of Europe once again. Louis XVIII became the restored King of France. Switzerland gained formal recognition as an independent confederation of states.

Two years later, the Swiss Federal Diet compiled a list of fallen and surviving Swiss Guards who had taken part in battles involving France. The Diet awarded the 389 surviving Swiss Guards a commemorative medal engaved Treue Und Ehre — Loyalty & Honor.

Pfyffer seized the moment to envision a monument to his fallen comrades. He published “An account of the bearing of the regiment of Swiss Guards on August 10, 1792″ in 1819, organized a subscription for funds, and began designing. A lion lays dying with his front paw resting on a shield decorated with French fleur-de-lys to represent Louis XVI. The shield cannot protect itself and relies on the lion, just as the king had to rely on the Swiss Guard. The second shield has the Swiss Cross.

Pfyffer persuaded Bertel Thorvaldsen, a Danish sculptor living in Rome, to create the design models. Thorvaldsen had never seen a lion. Pfyffer wanted the lion to be dead. Thorvaldsen refused, and the two agreed the lion would be depicted dying with the shaft of a spear in his back.

Luka Thorn, a local stonemason, did the actual sculpting. Some say Thorn thought Pfyffer didn’t pay him a sufficient fee, and that in retaliation, Thorn made the lion look more like a boar. [Personally, I don’t see the resemblance.] The monument is 10 meters long and six meters high with an inscription below listing the names of officers who died at Tuileries Palace.

The monument, dedicated to Helvetiorum Fedei ac Virtuti [to the loyalty and bravery of the Swiss], was unveiled on August 10, 1821. King Frederick VIII of Denmark observed that “no more fitting, more beautiful memorial could be imagined.”

Immediately, Swiss Liberals denounced the Lion Monument. At a time when an independent Switzerland was being born, the statue was a symbol of former close ties with France and counter-revolutionary ideals.

Yet, the Lion Monument was also movingly beautiful and an immediate tourist attraction now visited annually by over 1 million people.

In 1880 Mark Twain observed that “the commerce of Lucerne consists mainly in gimcrackery of the souvenir sort; the shops are packed with Alpine crystals, photographs of scenery, and wooden and ivory carvings. I will not conceal the fact that miniature figures of the Lion of Lucerne are to be had in them. Millions of them. But they are libels upon him, every one of them.

“There is a subtle something about the majestic pathos of the original which the copyist cannot get. even the sun fails to get it; both the photographer and the carver give you a dying lion, and that is all. The shape is right, the attitude is right, the proportions are right, but that indescribable something which makes the Lion of Lucerne the most mournful and moving piece of stone in the world , is wanting.” — Mark Twain, A Tramp Abroad.

And so, the lion continues to weep, touching hearts that know nothing of Swiss Guards and French kings, but recognize despair when they see it.

🦁 🦁 🦁

Illustrations

Europe. Attribution Gunasekhar Karri, 2010.

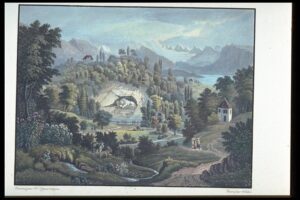

Lithograph. Lion Monument. 1840.

Dying Lion Statue in Lucerne by A. Savin, 2022.

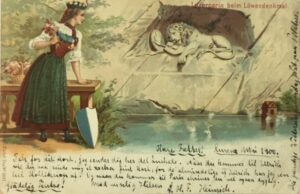

Postcard of Lion Monument, 1900.

Lion Monument. Photo by Author. 2023.

Olivier Pauchard. “The Lion of Lucerne: The Controversial Tourist Attraction. Swissinfo. Aug. 7, 2021.

Kira Kofoed. “The Dying Lion.” Thorvaldsen’s Museum Archives. 2013.

Mark Twain. Chapter 26, A Tramp Abroad. The Literature Network.

Sandra Wagner-Wright holds the doctoral degree in history and taught women’s and global history at the University of Hawai`i. Sandra travels for her research, most recently to Salem, Massachusetts, the setting of her new Salem Stories series. She also enjoys traveling for new experiences. Recent trips include Antarctica and a river cruise on the Rhine from Amsterdam to Basel.

Sandra particularly likes writing about strong women who make a difference. She lives in Hilo, Hawai`i with her family and writes a blog relating to history, travel, and the idiosyncrasies of life.

Aloha Sandra,

Love your blogs always, and this is another good one, but the illustrations bit does not match what is happening. Just wondering what is happening there.

Thanks,

Paula

Thank you for your comment. I agree with your sentiment. Unfortunately, I can’t always find illustrations that related most clearly to the text, so I try to find the closest ones I can.