In March 1974 peasants from Xiyang Village were sinking a well in an area south of their village. At the depth of 4.5 meters they encountered shards of pottery, bronze triggers and arrowheads, and a brick-paved floor. They reported their discovery to the Cultural Centre of Lintong County. The archeological team identified the pottery as connected to larger figures, and the bronze triggers to be crossbow triggers. Specimens went to the Cultural Relics Administration of Shaanxi Province.

Our guide reported that local authorities kept the discovery secret, but the news came out when a reporter based in Beijing returned home to visit his wife. At that time couples were often separated by work assignments. The reporter’s wife worked for the local government. It was he who made the report to Beijing. I don’t know if this is a true story, but I’m pretty sure a discovery of this magnitude wouldn’t remain secret for long.

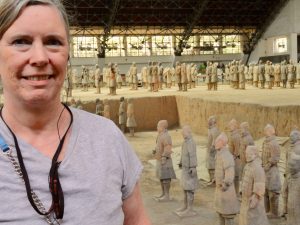

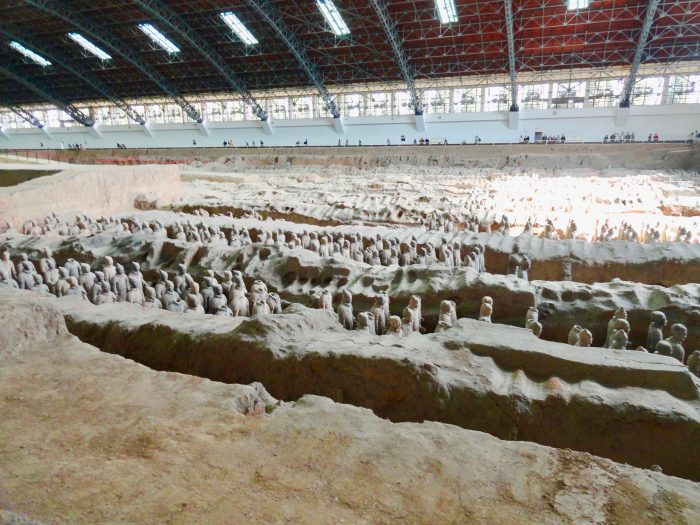

The central government built an exhibition hall to cover what is called Pit 1, an area of 2,000 square meters. Excavations began after its completion in 1978. Thus far about 1,000 soldiers and horses have been excavated and cleaned. An additional 5,000 are being processed. The army is placed in a rectangular formation facing east. The first three rows each have 210 warriors. These are followed by marching soldiers and horses drawing war chariots.

EMPEROR QIN SHIH HUANG

Emperor Qin Shih Huang assumed the throne in 259 BCE at about the age of 13. He immediately began constructing his tomb and the army that would defend him in the afterlife. Qin Shih Huang is also known as the First Emperor. From his base in the small state of Qin he unified China through force of arms and internal reforms, created one Chinese script, unified currency, standardized weights and measures, and even decreed uniform axle widths to make the roads less rutted. Qin Shih Huang is also credited with the Great Wall, though it was more a policy of joining existing walls. A fact that doesn’t make the process any less brutal.

In 210 BCE the emperor unexpectedly died during a tour of Eastern China. A power struggle ensued as did local rebellions. Though his tomb remains intact and is yet to be opened, marauding forces plundered Qin Shih Huang’s army, taking their weapons. Raging fires, probably deliberately set, weakened the support pillars for wooden ceilings over the troops which then crashed into the clay figures.

The soldiers became frozen in time, preserved in the dry underground environment. So dry, that when they were first discovered, the men still had their painted surfaces. Unfortunately, the more humid air at the surface caused much of the paint to disappear. Excavation stopped until a way could be found to preserve the color.

The soldiers became frozen in time, preserved in the dry underground environment. So dry, that when they were first discovered, the men still had their painted surfaces. Unfortunately, the more humid air at the surface caused much of the paint to disappear. Excavation stopped until a way could be found to preserve the color.

Archeologists have discovered over 600 pits, but only the Pits 1, 2, and 3 have yielded terra cotta treasure. The first pit is the most dramatic, yielding over 8 wooden war chariots, about 1,000 warriors and horses, and 30,000 bronze weapons. Excavations continue.

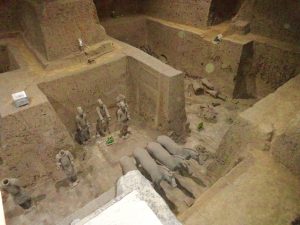

Pit 3 contained a wooden chariot and 72 warriors and horses. Excavation at Pit 2 reveals more about how construction may have looked. The wooden ceilings are still in place, covered with soil.

Pit 3 contained a wooden chariot and 72 warriors and horses. Excavation at Pit 2 reveals more about how construction may have looked. The wooden ceilings are still in place, covered with soil.

The privilege of seeing the Terra Cotta Warriors in person is one I’ll not soon forget. Though the viewing platform for Pit 1 is above the exhibition, it still felt as if I could reach out my hand and touch history.

Though there is an element of molds for the bodies, each face has individual features; each hair style is unique. The individuality of each soldier is unexpected. These aren’t people usually depicted, yet here they are. History come to life.

Though there is an element of molds for the bodies, each face has individual features; each hair style is unique. The individuality of each soldier is unexpected. These aren’t people usually depicted, yet here they are. History come to life.

Qin Shih Huang wasn’t a benevolent ruler. He crushed is opponents and cared little for those who labored on his projects. Ironically, it is those very craftsmen who are immortalized. It’s their faces we see as we look across this bridge into history.

??????

Illustration of Qin Shih Huang. Public Domain. Wikimedia Commons.

All other photos by Author. All Rights Reserved.

Qin Shi Huang Terracotta Warriors & Horses Museum. China’s Museum.

Arthur Lubow. “Terra Cotta Soldiers on the March.” Smithsonian Magazine. July 2009.

Yuan Zhongyi. The Terra-cotta Army of Emperor Qin Shih Huang. 1993.

Sandra Wagner-Wright holds the doctoral degree in history and taught women’s and global history at the University of Hawai`i. Sandra travels for her research, most recently to Salem, Massachusetts, the setting of her new Salem Stories series. She also enjoys traveling for new experiences. Recent trips include Antarctica and a river cruise on the Rhine from Amsterdam to Basel.

Sandra particularly likes writing about strong women who make a difference. She lives in Hilo, Hawai`i with her family and writes a blog relating to history, travel, and the idiosyncrasies of life.