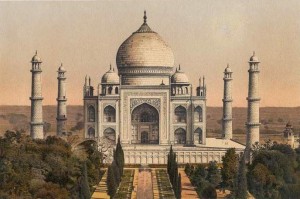

This is a story about gardens at the Taj Mahal, and the man who made them uniquely British. This photograph taken in 1874 shows something you don’t see in contemporary pictures. Very tall trees.

The Taj Mahal wasn’t just a mausoleum for Mumtaz Mahal. It was a Mausoleum and Gardens, equally important parts of a whole. Designers laid out Charbagh Gardens, a style that envisioned the gardens of Paradise. Such gardens were filled with fragrant flowers, voluptuous fruits and exotic birds. There were four rivers: one of water; one of milk; one of honey, and one of wine.

Gardens at the Taj Mahal covered an area 984 feet by 984 feet. Each smaller garden within the Charbagh was divided into sixteen flowerbeds for a total of sixty-four beds. The garden held four hundred plants. These included Cyprus trees symbolizing death and fruit trees representing life. Favored Mughal fruit trees were mango, lemon, and pomegranate. Sweet smelling hibiscus and jasmine plants perfumed the air.

As the foliage grew, it masked the monument, which revealed itself slowly to visitors.

As time passed, both the monument and the gardens fell into disarray. The approach, as described by Lord Curzon, was one of “dusty wastes and squalid bazaars.”

The first British effort to restore the Taj Mahal was undertaken by Lord Minto, Governor General (1807-1813). He raised funds by selling the garden’s produce and later attached the revenue from villages attached to the Taj Mahal. But any gains were short-lived.

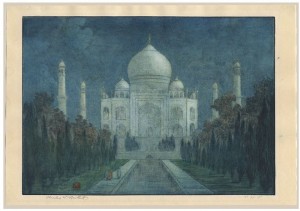

In the late nineteenth century, British visitors enjoyed picnicking on the grounds. When lunch was finished, they sauntered over to the monument with the chisels and dug out the precious stones and minerals that still remained. The mosque flanking the Taj Mahal and a guesthouse were rented out as honeymoon cottages. Fashionable society attended balls with music by a military band arranged on the platform.

Such pastimes stopped when Lord Curzon became Viceroy of India. Curzon was said to be an arrogant man. A parody of his days at Oxford depicted the young scion introducing himself: “My name is George Nathaniel Curzon, I am a most superior person.”

Nevertheless, Lord Curzon cared deeply about Indian monumental architecture, particularly the Taj Mahal which he visited annually. He believed the massive buildings testified to India’s ancient status and the British role as their guardian and preserver. In short, Curzon was on a civilizing mission. He was the first restorer to look at the gardens, and he was horrified.

Lord Curzon ordered the trees removed. In common with most British in India, he believed gardens should be flat and formal, paving the way to the monument. Gardens provided vistas, not texture. The flowers had to go too. Simple grass accented the waterways.

At the dedication of the restored Taj Mahal in 1909 Lord Curzon waxed poetic on his accomplishment. There was now a beautiful park, “and the group of mosques and tombs, the arcaded streets and grassy courts that precede the main building are once more as nearly as possible what they were when completed by the masons of Shah Jehan.” Lord Curzon might be forgiven if he thought the gardens even better than those of the Shah Jehan.

Lord Curzon personally funded parts of the Restoration. “Since I came to India we have spent upon repairs at Agra alone of sum of £40,000. Every rupee has been an offering of reverence to the past and a gift of recovered beauty of the future.”

In particular, Lord Curzon personally donated two chandeliers. When the Jats of Bharatapur invaded Agra in the eighteenth century, they took two chandeliers, one silver and one agate, from above the royal cenotaphs. Lord Curzon took it upon himself to procure replacements.

On his way home, Lord Curzon stopped in Cairo to procure a properly Saracenic lamp to hang in the tomb chamber. The bronze lamp, modeled after one that once hung from Sultan Baibars II’s mosque, is inlaid with gold and silver. Inscribed in a script that matched that of the original calligraphers, the engraving proclaims “Presented to the Tomb of Mumtaz Mahal by Lord Curzon, Viceroy 1906.”

The second chandelier, weighing one hundred thirty-two pounds, was placed in the Royal Gate, the entrance through which tourists pass into the grounds. Last August, the chandelier fell. No one was injured.

Acknowledgements:

Featured Image: Photo of Taj Mahal taken by Francis Frith in 1874. Public Domain. Wikimedia Commons.

Francis Frith (1822-1898) was a successful commercial photographer who noted that armchair travelers would purchase photographs taken away from the European tourist routes.

BBC. Taj Mahal Chandelier Crash Investigation Ordered. Aug 22, 2015. Here.

http://www.tajmahal.org.uk/history.html

“Garden’s in Agra’s Taj Mahal still feel British.”Economic Times. Here.

“When Taj was Green.” The Pioneer. May 26, 2013. Here.

Eugenia W. Herbert. Flora’s Empire: British Gardens in India. University of Pennsylvania Press. 2011.

Annabel Lopez. “Taj Mahal’s history of repair and restoration.” July 3, 2007. Here.

Rajaram Panda. Taj Mahal. New Delhi: Mittal Publication. N.D.

Sandra Wagner-Wright holds the doctoral degree in history and taught women’s and global history at the University of Hawai`i. Sandra travels for her research, most recently to Salem, Massachusetts, the setting of her new Salem Stories series. She also enjoys traveling for new experiences. Recent trips include Antarctica and a river cruise on the Rhine from Amsterdam to Basel.

Sandra particularly likes writing about strong women who make a difference. She lives in Hilo, Hawai`i with her family and writes a blog relating to history, travel, and the idiosyncrasies of life.

very interesting! too bad he destroyed all the plants Fragrant Hibiscus? native Hawaiian ones are the only ones I know of that are fragrant……

Ancestor plants of modern hibiscus include India as a home. Apparently a few hibiscus varieties do have a modest scent. Glad you enjoyed the blog.

A curse on Lord Curzon. We prefer trees and flowers.

I would love to have seen the luscious fruit trees and hear the singing birds.

Intresting … just as I was reading his two vol biography \”The Life of Lord Curzon \” by the Hon. the Earl of Ronladshay \” there is much more on this subject to read particularly onthe lamp he designed and that still hangs atop Mumtaz Mahal\’s grave .

keep writing and if you could find a picture of those times on the lamp it would be great .

Thank you so much for your comment.

Is this real did this really happen?

To the best of my knowledge, the blog is accurate. Thank you for your question.

Brilliant to read this.Speaking to my brother about Lord Curzon and he said when he visited the Tai Majal on a guided tour he cannot remember Lord Curzon\’s name being mentioned and as he donated £40,000 of his own money towards renovation he found this surprising.

Surprising but not unusual. Often the past is remembered selectively. Thanks for your comment.

My late Grandmother, Olive Curzon, claimed she was distantly related to Lord Curzon, and told me he never got any thanks when he did anything good, I think she was right, for example on Remembrance Day no one ever gives him credit for designing our tribute to the fallen.

Lord Curzon also sponsored the Victoria Memorial in Kolkata, which was then the capital of British India. By the time the memorial was finished in 1921, the capital had moved to New Delhi. It’s a museum now, & Lord Curzon’s name doesn’t come up. Thank you for commenting.