In 1929 Virginia Woolf published A Room of One’s Own in which she argued that if a woman is going to write fiction, she must have money and a room of her own. Woolf developed her theme by looking at female writers in history, many of whom did not publish their writings.

In her observations Woolf asserted that in her opinion, Aphra Behn turned an important the corner for female writers.

Mrs. Behn, Woolf wrote, was a middle-class woman with all the plebeian virtues of humour, vitality and courage; a woman forced by the death of her husband and some unfortunate adventures of her own to make her living by her wits. She had to work on equal terms with men. She made, by working very hard, enough to live on. The importance of that fact outweighs anything that she actually wrote.

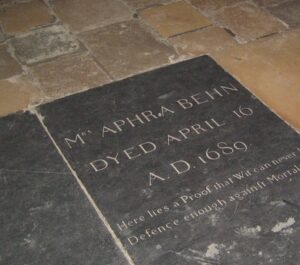

Aphra Behn, Woolf continued, opened the door for women to write as they pleased and earn money, despite the fact that Behn’s free lifestyle closed it again. Nevertheless, by the 19th century women began writing publicly. For that reason, Woolf claimed, All women together ought to let flowers fall upon the tomb of Aphra Behn, which is, most scandalously but rather appropriately, in Westminster Abbey, for it was she who earned them the right to speak their minds. Aphra Behn, shady and amorous as she was, made it possible for women to earn money by their wits.

Woolf’s acknowledgement brought Aphra Behn into modern academic discourse. Women wanted to know who this woman was and what made her shady.

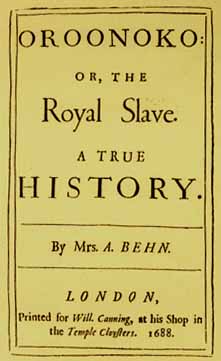

If nothing else, Aphra was adventurous. During her twenties she traveled to Surinam, a sugar colony in South America, with Bartholomew Johnson and his family. It’s thought that he died on the journey, though his wife and children remained in the country for a time. No one really knows. However, while Aphra was in Surinam she met an African slave leader who became the basis for her later novel Oroonoko. One of the first novels of ideas, Oroonoko called for the abolition of slavery before the anti-slavery movement had begun in England.

After her return to England, Aphra married a merchant, John Behn, who died shortly thereafter, possibly from the plague that was rampant in London in 1765-66. After her husband’s death, Aphra a staunch supporter of Charles II, became a spy in Antwerp during the Second Dutch-Anglo War. Her Code Name: Astrea.

Aphra’s mission was to establish a close relationship with a soldier named William Scot and turn him into a double agent. She was also supposed to report on any English exiles plotting against Charles II. There is some evidence Scot betrayed Aphra to the Dutch. In any event, Aphra returned to England and petitioned the king for payment, but never received it.

She did, however, obtain work for two theater companies: the King’s Company and the Duke’s Company. As a playwright, Aphra’s first commercial success was The Rover, or, The Banished Cavaliers in 1677. The play, revived for performance in the 1970s, is a bawdy Restoration comedy about the romantic intrigues of an English gentleman in Naples over carnival weekend. The play was a resounding success with a long run, and Aphra received a share of the box office proceeds.

Some of The Rover’s initial popularity can be traced to the actress Nell Gwyn, one of Charle II’s many mistresses, who took a major role in the production.

Over time, Aphra wrote 19 plays, in addition to novels and poems.

From Aphra Behn’s The Willing Mistress

Down there we sat upon the moss,

And did begin to play

A Thousand Amorous Tricks, to pass

The heat of all the day.

A many Kisses he did give:

And I returned the same

Which made me willingto to receive

That which I dare not name.

His Charming Eyes no Aid requir’d

To tell their softening Tale;

On her that was already fir’d,

’Twas Easy to prevaile.

He did but Kiss and Clasp me round,

Whilst those his thoughts Exprest:

And lay’d me gently onthe Ground:

Ah who can guess the rest?

Aphra died in 1689 and was buried in the East Cloister of Westminster Abbey. The inscription on her tombstone reads: “Here lies a Proof that Wit can never be Defence enough against Mortality.”

🌟 🌟 🌟

Illustrations

Aphra Behn by Peter Lely, c. 1670

A chart of Surinam, indicating different plantations and their owners. Between 1737 and 1757.

Cover: Oroonoko. 1688.

Nell Gwyn by Simon Pietersz Vereist.

Aphra Behn’s Grave. Photo by Tonya.howe.

Megan Rosenfeld. “The Bawdy Plays of Aphra Behn.” The Washington Post. Jan. 5, 1982.

Belinda Webb. “Aphra Behn: Still a Radical Example. The Guardian. Nov. 13, 2007.

Sandra Wagner-Wright holds the doctoral degree in history and taught women’s and global history at the University of Hawai`i. Sandra travels for her research, most recently to Salem, Massachusetts, the setting of her new Salem Stories series. She also enjoys traveling for new experiences. Recent trips include Antarctica and a river cruise on the Rhine from Amsterdam to Basel.

Sandra particularly likes writing about strong women who make a difference. She lives in Hilo, Hawai`i with her family and writes a blog relating to history, travel, and the idiosyncrasies of life.

I always enjoy your posts.

Thank you so much — I’m so glad you enjoy them.