When we think of women novelists writing in the English language, Jane Austin is usually the first name that comes to mind. It’s fair to say the Jane Austin was the first to have a popular impact, but the first female author writing in English was Mary Wroth (1587-1653). Jane Austin’s work came out 200 years later. I encountered Mary for the first time last week when I read an article about her in the Smithsonian Magazine. Intrigued, I did some research. It turns out Mary Wroth and her work is receiving academic notice, but particulars of her personal life remain a bit elusive.

Mary belonged to a literary family, which explains how and why she received an education at a time when even upper class women often remained illiterate. Mary’s aunt, the Countess of Pembroke, was Mary Herbert, a member of the Sidney family and a patron of writers. Mary’s uncle Sir Philip Sidney was one of the best known poets of Elizabethean England.

In 1602, at the age of 15, Mary made her first appearance on the public stage when she danced for Elizabeth I as part of the entertainment when the royal entourage stopped at the family seat Penshurst Place. When Elizabeth died in 1603, Mary became a member of Queen Anne’s circle of friends. The following year James I sponsored Mary’s marriage to Sir Robert Wroth.

The match had been in the works since 1599 when Mary was 12 years old. Wroth was the son of a wealthy landowner who caught James I’s attention due to his hunting skills. The king routinely visited Wroth’s homes at Durrance and Loughton Hall on his hunting expeditions. James rewarded Wroth’s service with a knighthood.

In addition to his skills on the hunt, Mary’s husband had a reputation as a gambler, philanderer, and drunkard. It wasn’t a happy marriage. Some sources say problems began when Mary’s father didn’t pay her husband the promised dowry.

Meanwhile, Mary had a longstanding friendship with her cousin William Herbert, Third Earl of Pembroke, who was one of the wealthiest men in England and popular at court. Herbert had a dubious reputation with women. As a young man, he had an affair with a woman named Mary Fitton by whom he had a child. Scandal enough, but though admitting paternity, he refused to offer her marriage. This resulted in a brief residence at Fleet Prison in 1601. Three years later, Herbert negotiated a marriage contract with Mary Talbot, daughter of the 7th Earl of Shrewsbury.

In February 1614, Mary gave birth to a son, James. She probably had other children as well. In March 1614, Mary’s husband died, ostensibly from gangrene. The estate passed to Mary’s son, and was in some sort of trust until James came of age. Wroth left his widow with an enormous debt of £23,000 [worth over £3 million in 2017]. Son James died in 1616, and the estate then passed to her husband’s next heir. [This situation often plays out in Jane Austin novels.]

After her husband died, Mary began a lengthy affair with William Herbert. The couple had two children: Catherine and William.

Deeply in debt, Mary turned to writing as a means of support, and in 1621 published The Countess of Montgomery’s Urania, largely based on her own life. The story refers to a jealous queen who exiles her weaker rival from the court in order to keep her lover. True? False? Who can say?

Primarily, the story focuses on the characters of Pamphilia, her cousin and best friend Urania, and Amphilanthus, Pamphilia’s unfaithful lover. Mary modeled Pamphilia after herself and Amphilanthus on her lover Herbert.

The title page illustration is an engraving of the Throne of Love, a central episode in the novel. The major characters find themselves on an island with a palace on a high hill. To reach the palace, the characters must cross a bridge topped with three towers. The first was Cupid’s Tower, aka the Tower of Desire, a place of punishment for false lovers. The Tower of Love belonged to Venus and could only be entered by those who overcame various threats such as Jealousy, Despair, and Fear. Constancy guarded the third tower and held the keys to the palace and the Throne of Love.

Mary wrote about the world she knew with themes of constancy and love. She depicted women who loved without fear, regardless of the consequences. One of the lesser stories concerned a woman who cheated on her jealous husband. When her affair became known, the woman’s father took her husband’s side and tried to kill her.

The story struck a nerve with Lord Edward Denny, Baron of Walton. When his daughter Honoria had an affair, he had had the same reaction. Denny was furious, because readers would know he was the subject of the story.

Denny was not the only nobleman incensed about topics Mary revealed about their lives while claiming her book was fiction.

Mary later wrote: “Strange constructions are being made of my book, contrary to my imagination.” In December 1621, Mary withdrew her publication and left the Court. About that time, Mary’s relationship with William Herbert also ended.

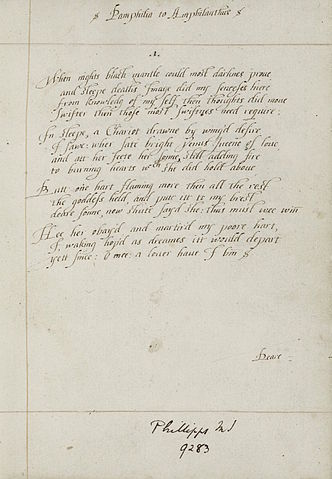

Sonnet 1, of Mary’s Poem Pamphila to Amphilanthus

When night’s black Mantle could most Darknesse prove*

And Sleepe (deaths Image) did my senses have,

From Knowledge of my self, then thoughts did move

Swifter then those most [swiftness] need require.

In sleepe, a Chariot drawn by wing’d Desire

I saw; where sate bright Venus Queen of Love,

And at her feet her Sonne, still adding Fire

To burning hearts, which she did hold above,

But one heart flaming more than all the rest,

The Goddess held and put it to my breast,

Dear Sonne now [shoot], said she: thus must we winne;

He her obey’d, and martyr’d my poor heart.

I waking hop’d as dreams it would depart,

Yet since, O me, Lover I have Beene.

Mary’s stories in Urania didn’t just expose incidents the people involved preferred to keep hidden, their existence placed a woman into public life at a time when poetry written and published by a woman was a direct affront to the social status quo.

Mary Wroth’s work was not ‘popular.’ It did not get her out of financial difficulty, and it did not remain in the public realm. But it continues to exist and reveals that the English Renaissance was not a male-only realm. I suspect this is why Mary’s work is becoming part of the academic canon.

*From Pamphilia to Amphilanthus

🎊 🎊 🎊

Illustrations

Portrait of Mary Wroth attributed to John de Critz.

Loughton Hall. Attribution: Lee Holmes.

William Herbert, Third Earl of Pembroke.

Title page of the Countess of Mountgomery’s Urania. 1621.

The First Sonnet in Lady Mary Wroth’s manuscript of Pamphilia to Amphilantus. Folger Shakespeare Library.

V. M. Braganza.” The Secret Codes of Lady Wroth.” Smithsonian Magazine. September 2021.

Nandini Das. “Women Writers to put Back on the Shelf: Lady Mary Wroth.” BBC Radio 3. Mar 3 2020.

Sandra Wagner-Wright holds the doctoral degree in history and taught women’s and global history at the University of Hawai`i. Sandra travels for her research, most recently to Salem, Massachusetts, the setting of her new Salem Stories series. She also enjoys traveling for new experiences. Recent trips include Antarctica and a river cruise on the Rhine from Amsterdam to Basel.

Sandra particularly likes writing about strong women who make a difference. She lives in Hilo, Hawai`i with her family and writes a blog relating to history, travel, and the idiosyncrasies of life.