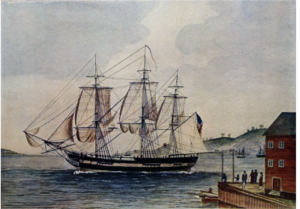

Writing historical fiction is tricky, particularly if the story is based on or inspired by real people. I’m currently writing the second book in my Salem Stories series based on the 18th century Crowninshield and Derby families of Salem, Massachusetts. The story is about real people in the context of their material culture. Both aspects require a fair amount of research before I write the actual story. It’s not enough to know what happened to whom. I need to know everything I can about objects and places relevant to the story, which brings me to the Belisarius, a merchant ship built by the Enos Briggs, a premier shipbuilder, for George Crowninshield & Sons. She was over 200 tons, copper bottomed, and pierced for 16 guns. She made her first voyage in November 1794 under the command of George Crowninshield, Jr. with his brother John serving as clerk. She was a fast ship, returning from her voyage in less than a year with a cargo of tea, coffee and indigo.

Sounds good. But I had a question. Every reference I read mentioned Belisarius had a copper bottom. Why was that so important? Turns out copper sheathing on a wooden ship’s bottom improved sailing performance, and protected the hull from both the corrosive effects of salt water and the biological hazards of barnacles and saltwater mollusks that laid their eggs in wood, which led to a honeycomb of tunnels. The British Navy began applying copper sheathing in 1761.

The reader doesn’t necessarily need or want to know about copper-bottomed ships. But as a writer, knowing why copper was used gave me insight into the type of meticulous merchants and shipbuilders the Crowninshields were.

Pictures are also helpful as I develop local backgrounds. Above, the Belisarius is shown leaving Salem Harbor from the Crowninshield pier at Union Wharf. For a vessel that made regular round trips from Salem to Europe, to Madeira, to Cape of Good Hope, to Mauritius, to Calcutta, and home again, she looks surprisingly small.

And what about ports of call?

One of my characters, Nathaniel Silsbee, wrote an autobiography for his family in which he described his voyage on the Benjamin in 1794. Various circumstances caused him to call at Dover harbor on the southeast coast of England.

What did Dover look like in 1794, a year after hostilities between England and France resumed? Dover, famous for its white chalk cliffs, was a garrison town with a harbor and what was once a defensive castle further up the hill. Piers at the time were insubstantial.

This type of painting helps me visualize what Dover looked like. The brig is coming towards the viewer; the fishing boat passes the ship as it enters the harbor, and the waves don’t look pleasant for either vessel. In the background, Dover’s famous white cliffs are easy to see.

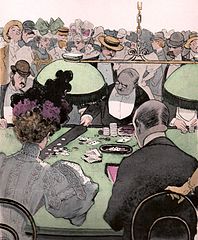

Nathaniel Silsbee wrote that he played cards at Dover for the first and last time in his life. The first night he played, Nathaniel acquired enough winnings for the other players to demand a rematch the second. Nathaniel deliberately lost his winnings from the previous night and walked away. He didn’t mention what card game he played.

It turns out that baccarat, a game that originated in Italy in the 15th century, was very popular at the time. Thus it seemed a reasonable choice for a scene featuring a young man from Salem who had never played cards before participating in a “friendly game.”

“Have some Madeira, m’dear”

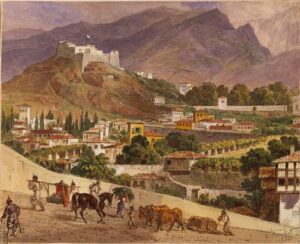

From Dover, Nathaniel Silsbee took the Benjamin south towards Cape of Good Hope. Along the way, he stopped at Madeira, a Portuguese colony, to load a cargo of Madeira wine. The fortified wine was a luxury drink in the 18th and early 19th centuries that came in a range of dry to sweet styles. The wine is heated during fermentation to create flavors of roasted nuts, peach, orange peel, caramel and toffee. The highest quality Madeira is made from four different varieties of grapes.

Madeira was also a good place to take on water and fresh food. The illustration on the right includes a cask of what could be Madeira wine.

It cannot be said that writers spend all their time studiously developing plot lines or doing research. I, like many other writers, follow key words into a maze of bizarre information. So, while deep diving into the particulars of Madeira wine and the size of wine casks, which can hold up to 7,920 gallons of wine, a bit of slap-happy silliness crept into my mind. In this case, I remembered the ditty Have some Madeira, m’dear released by Donald Swann and Michael Flanders in 1957.

If you have time for a bit of fun, check out this 1981 version by Lou Gottlieb and the Limeliters.

🍷 🍷 🍷

Illustrations

Belisarius leaving Salem, 1804.

A Brig Leaving Dover by George Chambers.

Catalan: Una Partide de bahada by Albert Guilaume, 1897.

Landscape on Island of Madeira by Karl Briulove, 1850.

Sandra Wagner-Wright holds the doctoral degree in history and taught women’s and global history at the University of Hawai`i. Sandra travels for her research, most recently to Salem, Massachusetts, the setting of her new Salem Stories series. She also enjoys traveling for new experiences. Recent trips include Antarctica and a river cruise on the Rhine from Amsterdam to Basel.

Sandra particularly likes writing about strong women who make a difference. She lives in Hilo, Hawai`i with her family and writes a blog relating to history, travel, and the idiosyncrasies of life.

Hi Sandra, What fun! I get the first part that the research can be quite something! So interesting what you write. And as we can see, almost all people worked incredibly hard prior to the life time we now live in, except of course the very wealthy always. My family in Finland survived all those years through the heavy winters, our family land is over 400 years with us, my cousin from the oldest son and family live there. He and his wife continued the dairy farm until they got too old, now they have a farm crop growing and no cows, none of the kids wanted to continue it, he is now 80. In the winter when not as much milk, he would go into the woods of the property and selective log and sell wood.

Great work, thank you so much!

Paula