A first glance, I wondered if I had arrived at the correct mountain top. The entrance turnstiles to Machu Picchu are a few yards away from the Sanctuary Lodge. Once visitors clear the entrance, they climb a short hill and suddenly the ancient city spreads out beneath one of the most famously photographed sites in the world. And, like most visitors, I couldn’t resist having my picture taken.

Access to Machu Picchu is different from that of other historical monuments. Visitors need their passports and tickets issued by name. If I said we needed passports, because we were entering a site of Incan power, that would be romantic, but it wouldn’t be true. Machu Picchu is a fragile monument. It accommodates 2,500 visitors per day. Authorities issue tickets for that purpose. Unfortunately, unscrupulous people once gathered used and/or discarded tickets and sold them at black-market prices. Clerks now match the name of the person to whom the ticket was issued to the passport

The origins and purpose of Machu Picchu are still not entirely understood, and I was fortunate to have Jose Angle Ayerbe as my guide into the past. The site is 7,970 feet above sea level on the eastern slope of the Andes Mountains. Despite the pills I took to prevent altitude sickness, I was very aware my usual elevation is sea level. It’s a good thing we had a lot of history to discuss, because my lungs needed frequent breaks. Much of what I’m sharing is from conversations with Jose.

Even with Machu Picchu spread out before me, it was difficult to grasp that the site covers 80,000 acres, including religious, agricultural, and residential areas. The religious center stands to the left in the above picture, and the residential areas in the lower elevations. The terraces were used both for small crops and also as retaining walls. Other agricultural areas were located off site.

Despite it’s massive size, Machu Picchu was not particularly important. Cuzco, capital of the Incan Empire, is located far below. There are various theories about Machu Picchu’s purpose – a religious center, a retreat for The Inca, or simply a defensive site. Not so much a fortress as, perhaps, an early warning system. The Incas had conquered or made alliances with most of the surrounding people, but they were uneasy about the Amazonian peoples. The lower portion of the site, has a perimeter wall, while the upper portion was protected by the cliff face. There were also watchtowers.

The Incans built Machu Picchu sometime in the fifteenth century and left the site before it was completed. Over time, vegetation reclaimed the area, and it disappeared from history until Hiram Bingham III began excavating what he called the “Last City of the Incas” in 1911.

Bingham was looking for a different place – Vilcabamba, the last Incan capital. From Cuzco he traveled through the Urubamba Valley asking villagers for reports about Incan ruins. Bingham encountered a man named Melchor Arteaga, who didn’t know anything about Vilcabamba, but could lead Bingham to Incan ruins. Arteaga charged Bingham fifty cents to lead him to the site. Fifty cents doesn’t sound like much to us, but to Arteaga it represented wages for two and a half days’ labor.

Bingham, Arteaga, and an interpreter spent two hours climbing up the mountain to a small hut occupied by a few farmers. From here, a boy led Bingham’s party to what Bingham called

“an unexpected sight, a great flight of beautifully constructed stone terraces, perhaps a hundred of them, each hundreds of feet long and 10 feet high. . . Suddenly I found myself confronted with the walls of ruined houses built of the finest quality of Inca stonework.”

Bingham believed he’d found Volcabamba. Bingham returned to the United States and raised funds from the National Geographic Society and Yale University to return to Machu Picchu in 1912. Bingham’s team excavated an estimated 40,000 artifacts. Some Bingham purchased outright; others were taken back to Yale for preservation. Artifacts from Yale were returned in 2012 and are now housed in a museum in Cuzco.

Such concerns seemed far away as I walked around the site. There was the man who, along with many other employees, spent his days pulling vegetation from between the stones.

And the awe I have for Incan engineers who leveled and terraced a mountain to create a city out of rock. Note also the amazing way they carved each stone to fit without mortar. The work was worth the effort, because it keeps buildings standing despite frequent earthquakes. The more important the building, the more seamless placement of stones.

Bingham called this building Casa de Inca – House of the Inca. He believed The Inca resided here. The structure stands at the upper level of the residential area and is actually part of a larger complex. There was an open courtyard where work and business took place, smaller rooms where people slept, a bathing area, an area to house servants, and even a small pen where animals could be kept prior to slaughter. But though the occupant was no doubt of high rank, he wasn’t The Inca.

I spent an afternoon and a morning at Machu Picchu. The time was too short. Yet, despite the need to go back down the mountain, I’m enriched for the experience. There are many reasons to visit Machu Picchu, but the most important is to expand your understanding of the peoples who came before.

Next Week – Galapagos Islands National Park

Acknowledgements:

Featured Image: Photo of Author at look-out point taken by Jose Angel Ayerbe.

Unattributed Photos by Author. All Rights Reserved.

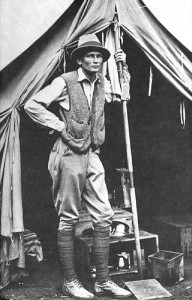

Photo of Hiram Bingham, US Public Domain, Wikimedia Commons.

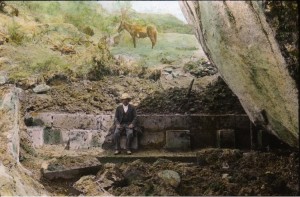

Harry Ward Foote was Bingham’s expedition collector & naturalist in 1911. Photo taken from hand-colored glass slide. Public Domain. Wikimedia Commons.

Hiram Bingham, “In the Wonderland of Peru.” National Geographic. 1913. Here.

Richard Cavendish. How Hiram Bingham discovered the ‘lost city of the Incas.’ History Today. Vol 61, Issue 7, July 1911. Here.

Whitney Dangerfield. Saving Machu Picchu. Smithsonian.com. April 30, 2007. Here.

Travel Details:

Belmond Sanctuary Lodge, Machu Picchu. Here.

Travel Arrangements:

Silversea Cruises Here.

Akorn Destination Management Here.

American Airlines and their One World Partner LAN

Sandra Wagner-Wright holds the doctoral degree in history and taught women’s and global history at the University of Hawai`i. Sandra travels for her research, most recently to Salem, Massachusetts, the setting of her new Salem Stories series. She also enjoys traveling for new experiences. Recent trips include Antarctica and a river cruise on the Rhine from Amsterdam to Basel.

Sandra particularly likes writing about strong women who make a difference. She lives in Hilo, Hawai`i with her family and writes a blog relating to history, travel, and the idiosyncrasies of life.

fun!