Over the years, historians have shared stories about the multi-cultural harvest event that took place in Plymouth in 1621. The usual version is that when the Pilgrims arrived on Cape Cod, the Wampanoag People showed them how to plant corn, and that when the harvest came in, everyone celebrated. If you don’t look too closely, it’s a true story.

Using a popular search engine, I researched several versions of those events. First, it should be noted, the Pilgrims didn’t mean to land at what became Plymouth, Massachusetts. When they boarded the Mayflower, they expected to arrive in Northern Virginia, which extended as far north as the Hudson River where they hoped to land. However, after a rough crossing, the vessel made landfall at Cape Cod. Attempts to sail south were thwarted by rough seas, and after almost being shipwrecked, the Pilgrims turned back to Cape Cod.

The Pilgrims weren’t in very good shape when they came ashore. They thought the weather would be warmer, and that they would be arriving at an existing colony, so they weren’t well-prepared. In fact, they were out of food. The first Pilgrims came ashore on Dec. 16, 1620, searching for food. The armed company found deserted houses and burial sites which they broke open and ransacked. After two days, the men returned to their ship with 10 bushels of maize.

The site the Pilgrims selected a site for their new village was an abandoned Patuxet settlement, which meant the surrounding fields were ready for agriculture. Fresh water was readily available. The Pilgrims also had an eye for defense, so they named the site for the village Cole’s Hill, and a higher site for their cannon, Fort Hill. They called their new village itself Plimoth.

On Dec. 21st, a landing party arrived to begin construction. As building progressed, twenty men stayed ashore to secure the village at night. Everyone else went back to the Mayflower. Women, children, and those who were ill never left the ship. At the end of Jan. 1621, settlers began unloading the Mayflower.

Five years previously, the coastline was densely populated by the Wampanoag People who controlled the area. The Wampanoag traded with Europeans, exchanging beaver pelts they considered worthless for steel knives and axes, copper kettles, and colored glass. The Wampanoag then exchanged goods with people further west. The Wampanoag did not allow Europeans to remain ashore, and they didn’t allow the Narragansett or other peoples to participate directly in the trade.

But disease decimated the Wampanoag population to a point that made them vulnerable to pressure from the Narragansett. Allowing the Pilgrims to remain with a mutual protection agreement was a strategy that might restore the power balance.

Massasoit, the Wampanoag sachem, planned carefully. He had two men who could act as interpreters. One was Samoset, sachem for an allied group. The other was Tisquantum, whom the Pilgrims called Squanto. Massasoit thought Tisquantum might be unreliable, but he had better language skills than Samoset.

On March 17th, Samoset walked into the Pilgrim village and began speaking English. The Pilgrims were astonished. Samoset spent the night, and left with presents. He returned the next day with five more men. More conversation took place.

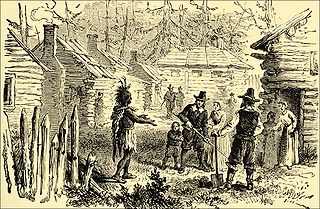

On March 22nd, Massasoit and his men hid from view while Samoset and Tisquantum walked into the village. By now, the Pilgrims were somewhat accustomed to these unannounced visits. After about an hour, Massasoit revealed himself and his warriors at the crest of a hill. The English were terrified and withdrew to Fort Hill. A standoff ensued.

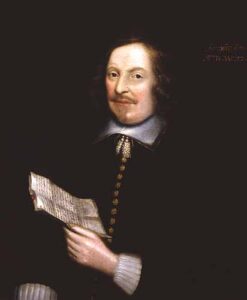

Edward Winslow decided to take action. He put on full armor. Carrying a sword, he waded across a stream between the two groups and offered himself as a hostage. In response, Massasoit, Tisquantum and 20 men crossed the stream. Talks took place. Eventually, the Pilgrims, in the name of England, and the Wampanoag made a treaty for mutual protection. Tisquantum remained with the Pilgrims and taught them how to hunt and plant corn.

During the ensuing months, the Pilgrims learned how to survive, and when the corn harvest came in, they celebrated. Winslow wrote: “Our harvest being gotten in, our governor sent four men on fowling, that so we might after a special manner rejoice together, after we had gathered the fruits of our labors; they four in one day killed as much fowl, as with a little help beside, served the Company almost a week, at which time amongst other Recreations, we exercised our Arms, many of the Indians coming amongst us, and amongst the rest their greatest king Massasoit, with some ninety men, whom for three days we entertained and feasted, and they went out and killed five Deer, which they brought to the Plantation and bestowed on our Governor, and upon the Captain and others.”

But There’s a Twist to the Story

It’s always seemed a bit strange to me that the English invited the Wampanoag to a feast, but only the warriors attended. Here’s another description of the events. The Pilgrims, understandably, were delighted with their first successful harvest, and celebrated with great enthusiasm—shooting their guns and cannon was part of the fun.

When the Wampanoag heard shots fired, they didn’t know what was going on. Who were the English shooting at? Massasoit gathered 90 warriors and went to Plimoth on a fact-finding mission. The translator, possibly Tisquantum, explained it was a harvest celebration. The Wampanoag decided to camp nearby and make sure this was true. The warriors hunted and gathered food: deer, ducks, geese, and fish. The Wampanoag stayed three days, satisfied themselves nothing threatening was going on and went home.

Happy Thanksgiving!

🦃🦃🦃

Illustrations

Adult Male Wild Turkey by Frank Schulenburg

First Thanksgiving 1621 by Jean Leon Gerome Ferris

Mayflower in Plymouth Harbor by William Halsall

Beaver by Greg Schechter

Samoset Speaks to Pilgrims

Edward Winslow

Indian Corn

Becky Little. “A Few Things You (Probably) Don’t Know About Thanksgiving.” National Geographic. Nov. 20, 2018.

Charles C Mann. “Native Intelligence.” Smithsonian Magazine. December 2005.

Gale Courey Toetsing. “The First Thanksgiving was a Fact Finding Party.” Indian Country Today. Nov 23, 2017.

Sandra Wagner-Wright holds the doctoral degree in history and taught women’s and global history at the University of Hawai`i. Sandra travels for her research, most recently to Salem, Massachusetts, the setting of her new Salem Stories series. She also enjoys traveling for new experiences. Recent trips include Antarctica and a river cruise on the Rhine from Amsterdam to Basel.

Sandra particularly likes writing about strong women who make a difference. She lives in Hilo, Hawai`i with her family and writes a blog relating to history, travel, and the idiosyncrasies of life.