After our first expeditions ashore on West Falkland, Le Lyrial began a journey of two days across the Scotia Sea to South Georgia. Scotia Sea, which covers the waters between Drake Passage, Tierra del Fuego, South Georgia, the South Sandwich Island, the South Orkney Islands, and Antarctica, was our first experience in choppy ocean water. Everyone on board quickly applied the “sea-sickness patch” to stave off symptoms of sea sickness. As we gained a semblance of sea legs, waves crashed into the side of the ship.

On the second day, Shag Rocks broke up the ocean view. The rocks, located 150 miles west of South Georgia and 620 miles from the Falklands, are a fragment of the Andes mountains that was left behind when the continents drifted apart.

South Georgia

Sixty percent of South Georgia is covered by glaciers, a “chilling” fact when you think of it. Though the island may have been discovered in the 17th century, it wasn’t until 1775, while on his return to the Sandwich Islands in the Pacific Ocean, that Captain James Cook made landfall and claimed the island for Britain. Why name the island South Georgia?😉 Perhaps because George III was the British king, and there was already a North American colony named Georgia.

Sealers and whalers frequently passed the island hunting for marine prey until in 1904 a Norwegian company created a more permanent presence by setting up the first whaling station at Grytviken. Five more whaling stations along the northeast coast soon followed. The stations closed in 1965 when there were too few whales left in the region for the industry to make a profit. From 1904 to 1965, over 175,000 whales passed through the processing plants.

Today the whaling stations’s collapsing toxic structures continue deteriorating, their machinery wrapped in asbestos. At Grytviken in 2003, there was a major asbestos removal project, and some buildings at Grytviken are now being used.

[Sidebar: in 1979 Christian Salvesen contracted with an Argentinian scrap metal merchant to salvage metal from the whaling stations on South Georgia. Under the guise of inspecting scrap metal at Leith, Argentinean forces landed on South Georgia igniting the 1982 Falklands War between Argentina and Great Britain.]

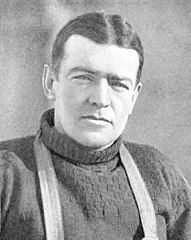

Ernest Shackleton — Heroic Explorer & Management Model

Though he was not the first man to reach the South Pole, Ernest Shackleton is perhaps the best known explorer associated with Antarctica. Shackleton led the Imperial Trans-Atlantic Expedition 1914-1917. The expedition employed two ships: The Endurance would take the main party to Vahsel Bay via the Weddell Sea. From there, Shackleton would lead a team of six men across the continent. A second ship, the Aurora, would take another party to McMurdo Sound on the other side of Antarctica, and set up supply depots so Shackleton’s party could complete their cross-continental journey.

On Dec. 5, 1914, the Endurance left South Georgia, despite warnings that the ice pack could trap the ship. By Jan. 19, 1915, the Endurance was frozen in an ice flow in the Weddell Sea, essentially trapped until the spring thaw. The Endurance drifted northward with the ice. In September, the ice began breaking up. The ship’s hull weakened under pressure from the ice and its movements. On October 24, 1915, a wave rippled across the ice. It lifted the Endurance‘s stern and tore off its rudder and keel. Shackleton gave the order to abandon ship. The Endurance sank on November 21. One could say it was a discouraging situation.

For the next two months, the explorers camped on the ice flow, hoping to drift towards Paulet Island, a known depot for supplies. By March 17, 1916, the men were only 60 miles from the island, but couldn’t reach it through the ice. On April 9th, the ice flow broke. Shackleton ordered his crew into the three lifeboats. After five days at sea, the men landed at Elephant Island. This was not particularly auspicious, because Elephant Island was too far from shipping routes to expect anyone to find them. The good news: the men were on land and still alive. The bad news: it seemed likely they would die on the island.

Shackleton decided to risk an open boat journey to South Georgia. He selected the sturdiest of the three lifeboats, christened it the James Caird after one of the expedition’s financial backers, and chose five men to join his rescue expedition. The remaining 22 men stayed at Elephant Island. Whether going to sea, or staying on land, the men must have thought their future was hopeless. What was the likelihood the James Caird would reach viable land? And if it did, would anyone return for them?

Shackleton took provisions for four weeks: 33 gallons of water, 250 pounds of ice, a sextant, a sea anchor, binoculars, and charts. The James Caird put to sea on Apr 24. For 15 days it managed to avoid capsizing until finally, on May 8, South Georgia came into sight. On May 15, the men established a camp on at the North side of King Haakon Bay which was on the southern shore of South Georgia. The whaling stations the men needed to reach were on the other side of the island.

Shackleton selected two men to traverse the island with him. Each carried his own rations. They also took a Primus lamp with oil, a small cooker, a carpenter’s adze to cut the ice and an alpine rope that could reach a full length of 50 feet. As they walked, they realized they were traveling on glaciers. It took 36 hours to reach the whaling station at Stromness on May 20. What a sight they must have been with their tattered clothes and emaciated bodies. The first people Shackleton encountered ran away.

Eventually the men reached the wharf at Stormness, and and an employee took them to station manager Thoralf Sørlie’s house. The employee knocked on the Sørlie’s door introducing the . . .

“three funny looking men outside, who say they have come over the island and they know you. I have left them outside.”

When Sørlie came out, Shackleton asked “Do you know me?”

Sorley replied he recognized the voice.

“My name is Shackleton,” his guest replied.

Shackleton noted that after a meal, a bath, and a change of clothes, “we had ceased to be savages and had become civilized men again.”

Shackleton immediately sent a boat to pick up the men he left on the other side of South Georgia, and began organizing the rescue of the men left behind on Elephant Island. After three failed attempts, Shackleton appealed to the Chilean government for assistance and rescued all 22 men on Aug, 30, 1916. They had remained in isolation for four and a half months.

Assessment of Shackleton’s Leadership & Management Skills

As Nancy Koehn, a historian at Harvard Business School, notes Shackleton, while not always making the best decisions, pivoted as circumstances required for the best possible result.

High on the list of poor management decisions was Shackleton’s decision to disregard warnings from experienced seamen that the pack ice was unusually thick, and that if the wind or temperature suddenly changed, the Endurance could be trapped in the ice.

However, when ice trapped the Endurance, Shackleton rose to the challenge and shifted his attention to the goal of remaining with the ship until the spring thaw released it and getting his crew home. To do this, he needed to keep the men’s spirits up.

Recognizing the potential danger of cramped quarters and enforced idleness was greater than the ice and cold, Shackleton kept up a daily routine. Each man performed his usual duties. Decks were swabbed. Scientists gathered specimens from the ice. Hunters brought back seals and penguins for food. Meals were served at the usual time, and the men socialized after dinner. Initially, not all the men would eat penguin, because superstition said penguins had the souls of lost sailors. Eventually, hunger trumped superstition.

When forced to abandon the Endurance to camp in tents on the ice flow, Shackleton knew his behavior and confidence would affect his men. So he projected confidence that they would all survive and make it home. The men knew their leader’s absolute commitment to their survival.

The contemporary management lesson of Shackleton’s success is that a leader must be committed to a larger purpose and use of flexible, imaginative methods to achieve it.

In 1921 Shackleton embarked on his last expedition to Antarctica and arrived at South Georgia on Jan. 4, 1922. He died of a heart attack the next day. While his remains were enroute to England, a message from Shackleton’s widow requested that her husband be buried on South Georgia. He was interred at the Grytviken cemetery on Mar. 5, 1922.

Grytviken no longer has permanent residents, but a few people live there during the summer months to manage the South Georgia Museum. It is a popular stop for cruise ships in Antarctica; passengers can disembark to visit the museum and pay their respects to Shackleton’s gravesite. Such a visit was on our itinerary, but wind and sea had other plans.

The word describing my second cruise lesson is Endurance. Set a realistic goal, adjust as needed, and never lose sight of what is truly important. Business schools use Shackleton’s loyalty to his crew and their successful rescue is a case study of successful management skills. I suppose the lesson is that with endurance even the most negative outcome can be managed.

On Mar. 5 2022, the Endurance22 Expedition located the Endurance‘s underwater resting place four miles from where she sank.

illustrations

Routes of ships Endurance & Aurora. Public Domain, modified by Finetooth.

Endurance sinking in Antarctica 1915.

Elephant Island Party by Frank Hurley 1916.

Launch of James Caird from shore of Elephant Island 1916.

Ernest Shackleton at Ocean Camp, Weddell Sea, 1915..

Panorama view of Grytviken by Jens Bludau.

Shackleton’s grave at Grytviken by Lexaxis7.

Nancy F. Koehn. “Leadership Lessons from the Shackleton Expedition.” New York Times. Dec. 24, 2011.

Kieran Mulvaney. “The Stunning Survival Story of Ernest Shackleton and His Endurance Crew.” History. Mar. 9,2022.

Sandra Wagner-Wright holds the doctoral degree in history and taught women’s and global history at the University of Hawai`i. Sandra travels for her research, most recently to Salem, Massachusetts, the setting of her new Salem Stories series. She also enjoys traveling for new experiences. Recent trips include Antarctica and a river cruise on the Rhine from Amsterdam to Basel.

Sandra particularly likes writing about strong women who make a difference. She lives in Hilo, Hawai`i with her family and writes a blog relating to history, travel, and the idiosyncrasies of life.