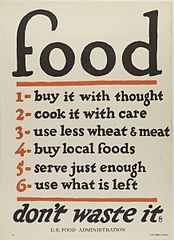

Except for point number 5 advising less wheat and meat products, this 1917 poster for about the acquisition, preparation, and consumption of food is similar to advice we receive today. Number 6, “use what is left” is tricky, because it refers to the dreaded food category of “leftovers.”

One 1948 cook book observed, the word “leftovers” brings an unpleasant mental picture “of a lot of odds and ends of food someone else didn’t want, mixed together with plenty of salt — boiled in a pot, and served on heavy, blue, restaurant china.” The same is true today. Yet, we carefully save uneaten food in plastic containers that float around the refrigerator until they are finally thrown out.

But this attitude towards leftovers didn’t always exist. In the 19th century, leftovers were a basic part of everyone’s diet. Breakfast was usually whatever food remained from the day before. Stews of varied ingredients simmered on the stove. These food choices weren’t about conservation. There simply wasn’t a realiable way to preserve food. Women (who were generally held responsible for all food preparation) routinely pickled, potted, smoked, salted, and preserved food in various containers until it could be consumed.

Habits began to change in middle and upper class homes during the 1890s with the advent of the Icebox. This marvelous invention was a food storage cabinet made of wood with a tin or zinc lining packed with straw, sawdust, cork or seaweed for insulation. The main attraction was a compartment for an ice block that kept food cool. Cheaper iceboxes had a drip pan that had to be emptied daily. Iceboxes on the higher end featured a spigot that drained melted ice into a holding tank. Suddenly, perishable food could be kept for several days.

In 1910, home refrigerators became available to the very wealthy. Suddenly, serving leftovers was a status symbol. A refrigerator company commissioned Left Over Foods and How to Use Them, a pamphlet that explained what to do with the new opportunity to serve food in the same way it had been originally prepared. Upper and middle class Americans eagerly puchased refrigerators as a new status symbol.

World War I changed public attitudes about leftovers. One of the consequences of being able to keep food, was the tendency to prepare more food than was necessary. Americans were urged to conserve food and use every crumb in goulashes or casseroles. Nothing should be wasted.

At least not until the 1920s, when Americans had money to spend on consumer goods, particularly refrigerators, and food prices fell. Since refrigerators were common and food was cheap, the new mantra was to be so wealthy it wasn’t necessary to eat leftovers.

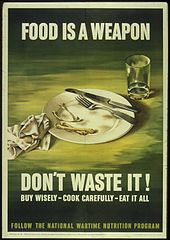

The boasting lasted until the 1930s when America fell into an economic depression. Leftovers, once again, symbolized virtue and thrift. But there was no reason they had to be boring. Food remnants could be reborn in a sauce, hidden in pot pies, or molded into meatloaf. The trend continued into World War II, when once again Americans were urged to use every scrap of food, so surplus rations could be sent to the troops or to refugees.

When World War II ended in 1946, factories retooled to produce consumer goods, the economy boomed, and food prices fell. In 1940, 50 percent of American homes had a refrigerator; in 1944, 85 percent of American kitchens included a refrigerator.

By 1960, Americans had a new view of leftovers, especially those found in the back of the fridge. “When in doubt, throw it out.” It’s not bad advice, but it also reflects that consuming leftovers wasn’t as necessary as it had been.

Cookery Books

These trends are reflected in popular cookbooks. When Irma S. Rombauer published the first edition of Joy of Cooking in 1931, the handbook included a listing of recipes suitable for leftovers.

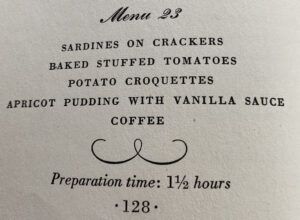

In 1948 a popular cookbook called Cooking by the Clock featured entire menus, with preparation times, so the family cook could present meals in which all the menu items were ready at the same time. One menu focused on a main course featuring leftovers.

I, don’t find this to be a particularly appetizing menu. And, one and a half hours to prepare dinner seems a bit much, but it was 1948. The authors point out that this menu was carefully constructed. “Prepare it just as it’s written and you’ll break down the most finicky of appetites. It’s the little extra touches that make the difference. The sardines will stimulate the taste buds —the baked tomato will furnish eye appeal—and the sweetness of the apricot pudding will give the meal the piquancy any good meal needs.”

The recipe for stuffed tomatoes calls for one cup chopped cooked or leftover meat (ham, tongue, chicken, veal, etc.) If the only leftover used is the meat, I’m not sure this is a recipe about leftovers, however, it does demonstrate that times had changed. Leftovers had lost their virtue and should not be noticed.

Two years later, Rombauer noted that too much budget cooking would only cause family protests. When the 1963 edition of Joy of Cooking came out, Rombauer’s daughter condensed the section on leftovers. Since then, refrigerators have become larger; leftovers reside in cute, matching containers until eaten or tossed, and microwaves make reheating their contents a quick and easy snack.

🍅 🍅 🍅

Illustrations

Food, Don’t Waste It. 1917.

1920s Icebox by Ferna.

1936 Refrigerator.

Give It Style. 1940s.

Food is a Weapon. 1940s.

Tomates farcies prêtes à passer au four by r.g-s

Food refrigerated in plastic containers by Kathleen Franklin.

Title Page. Cooking by the Clock. Farrar, Straus & Company. 1948.

Menu. Cooking by the Clock. Farrar, Straus & Company. 1948. page 128.

Helen Veit. “Economic History of Leftovers.” The Atlantic. Oct. 7 2015.

Sandra Wagner-Wright holds the doctoral degree in history and taught women’s and global history at the University of Hawai`i. Sandra travels for her research, most recently to Salem, Massachusetts, the setting of her new Salem Stories series. She also enjoys traveling for new experiences. Recent trips include Antarctica and a river cruise on the Rhine from Amsterdam to Basel.

Sandra particularly likes writing about strong women who make a difference. She lives in Hilo, Hawai`i with her family and writes a blog relating to history, travel, and the idiosyncrasies of life.

Hi Sandra,

Wow, those are huge tomatoes! Leftovers perhaps in regular American families were a bore, but there were many others and other cultures who utilized everything. In my parents-in-law home here in Kurtistown, they still had the icebox cabinet in 1982, just used for storage against rats at that point. Being immigrants, our family always used leftovers although there were rarely any, and I always take home food from restaurants (although there was a period of time, like you said, where it was all frowned upon), and have utilized leftovers fully through the years of raising kids and all. Thank you much for your blog!!

Hi Paula — I always enjoy the insights your comments bring. I think when there are teen-agers in the house, leftovers are soon snapped up as snacks. I also remember the years when leftovers were a vital part of menu planning. Thanks for commenting.