I’m writing a story that occurs in Salem, Massachusetts between 1760 and 1820. It’s an interesting period in American history, a time when English people in North America decided to break away from Great Britain. The famous skirmishes at Lexington and Concord took place in April 1775, and agitated citizens of Massachusetts began choosing sides in the upcoming conflict. The “rebels” organized a Provincial Congress led by its president John Hancock. People who supported the existing system began fleeing from rural areas surrounding Boston into Boston itself. One of these was Lady Frankland.

Lady Franklin & the Provincial Congress

In the midst of discussions about munitions and weapons, the Provincial Congress considered Lady Frankland’s migration from Hopkinton to Boston on two consecutive days. These sorts of unexpected discoveries are what make research through tedious records worthwhile.

As recorded in Provincial Congress notes from Thursday, May 18, 1775 “Committee to consider resolve of the Committee of Safety regarding Lady Frankland. Some excitement arose from inhabitants of the vicinity from the preparations made for her departure. An armed party arrested her journey and detained her person and effects until the action of Congress liberated them from captivity. The censure so lightly inflicted seems to have been incurred for the indiscreet zeal which interposed to prevent the enjoyment of the privileges granted by the resolve.

Resolved, that Lady Frankland be permitted to go into Boston with the following articles, viz: 7 trunks; all the beds and furniture to them; all the boxes and crates; a basket of chickens & a bag of corn; 2 barrels and a hamper; 2 horses and 2 chaises and all the articles in the chaise except arms and ammunition; 1 phaeton; some tongues, hams and veal; sundry small bundles. Permitted to carry them in without further examination.”

Clearly, Lady Frankland was moving her household to Boston. Unfortunately, the permission to move to Boston didn’t solve Lady Frankland’s dilemma, because on Friday, May 19, 1775 a second resolution is recorded.

“Resolved that Col. Bond be and is hereby directed to appoint a guard of 6 men to escort Lady Frankland to Boston with such effects as this Congress have permitted her to carry with her; and Col. Bond is directed to wait on Gen. Thomas with a copy of the resolves of this Congress respecting Lady Frankland.

Resolved that all persons who may have any goods or chattels belonging to Lady Frankland now in their custody which are not mentioned in the resolve of this Congress for allowing her with certain effects to go into Boston, be and hereby are directed to permit her to send them to Hopkinton or dispose of them in any way agreeable to her not inconsistent with the resolves of this Congress.”

My Search for Lady Franklin

At this point, I was officially intrigued and turned my attention to Lady Frankland. Who was this mysterious lady? We have several glimpses of her background, but the stories conflict.

Agnes Surriage was born in either 1724 or 1726 in Marblehead, Massachusetts. Her father was a fisherman. Her mother was born in Maine to a respectable family. Like almost every family, Edward and Mary Surriage had at least eight known children. Finances were tight, so when Agnes was old enough to work, her parents sent her to the Fountain Inn in Marblehead, where she worked as a maid.

In 1742, when Agnes was either 14 or 16, depending on which birthdate is correct, Agnes caught the eye of Sir Charles Henry Frankland, a Boston customs officer known to his friends as Harry.

Harry was heir to the baronetcy of Thirkleby in North Yorkshire, England, had plenty of funds, and was received by the high social circles of Boston. An innkeeper’s scullery maid was not the usual focus of his attention.

In the course of his official duties, Harry stayed at the Fountain Inn where he noticed the pretty, barefoot maid, and gave her money so she could buy shoes. On his next visit, Harry saw Agnes wasn’t wearing shoes and asked what she did with the money. Agnes claimed she bought shoes, but saved them to wear to church on Sundays.

It seems Harry was interested in more than Agnes’s feet. There is some evidence that she became pregnant and had a son who was named Henry Cromwell [Harry’s family name]. Other stories agree Harry had a son, but say the boy was from a previous relationship, and still other stories say the boy was his sister’s son. All we know for sure is that there was a boy named Henry Cromwell who was related to Harry.

Agnes was completely illiterate and untrained in social graces. In a spirit of generosity, Harry contacted Agnes’s parents and offered to take the girl to Boston as his ward. Harry promised he would educate Agnes, and boarded her with a family while she attended Peter Pelham’s School. After Agnes finished her education, she became Harry’s mistress. Boston society did not approve, especially after Harry came into his title in 1746.

To avoid further social embarrassment, Harry decided the best thing to do was purchase about 400 acres of land in Hopkinton, a town 30 miles away from Boston. Here he built a manor house and a plantation employing 12 enslaved people. The unconventional couple cultivated orchards and organized musical evenings and other entertainments.

When Harry’s uncle died, elevating Harry to the title Baronet of Thirkleby, there were problems with the will. The late baronet’s widow produced a document leaving the entire estate to her. Harry and Agnes went to England to settle legal matters, but lost the contested property. The couple then embarked on a tour of Europe.

On November 1, 1755, the day of the Great Lisbon Earthquake, Harry and Agnes were in Lisbon. Legend suggests that just before the earthquake struck, Harry was seen riding in a carriage with an unidentified woman. At any rate, when the earthquake struck, Harry, the woman, the carriage, the driver and the horses were all buried in rubble from a collapsing wall. Harry’s companion, in her panic, bit through the broadcloth of Harry’s coat and took a piece of flesh off his arm. Some say that while under the wreckage, Harry vowed that if he got out alive, he would marry Agnes. Meanwhile, Agnes refused to accept Harry’s death. She picked through the rubble until she heard a sound, persuaded men nearby to dig at the site, and rescued Harry.

Harry immediately took Agnes to the nearest Catholic priest and married her. Six months later the couple married again in a Church of England service.

The following year, Harry and Agnes returned to Boston. The couple purchased what is now called the Clark-Frankland Mansion, a 3-story, 26-room house in Boston’s North End. As the wife of a baronet, Agnes was accepted into all social circles.

Two years later Harry was named Consul General in Lisbon. He served six years before retiring to Bath where Harry died on January 11, 1768. Agnes was now a wealthy widow with the house in Boston, the plantation in Hopkinton, and a large annuity. Agnes returned to Massachusetts spending her winters in Boston and her summers in Hopkinton.

Agnes probably had only recently relocated to her summer home when events occurred at Lexington and Concord in April 1775. As the situation escalated, she decided to return to Boston and applied to the Provincial Congress for permission to transfer her household.

Shortly after the British defeated the American insurgents at the Battle of Bunker Hill on June 17, 1775, Agnes decided to return to England. She lived with Harry’s family and Henry Cromwell until she remarried in 1782 to John Drew, a banker in Chichester. Agnes died from pneumonia a year later and was buried at St. Pancras Church, Chicester. She was about 59 years old.

The Legend of Lady Frankland

The story of the poor scullery maid elevated to noble status was extremely popular in the 19th and early 20th centuries. In 1862, Oliver Wendell Holmes included a ballad Agnes in six parts as part of his Songs of Many Keys.

More recently, F. Marshall Bauer likens Agnes’s determination to survive and thrive to that of codfish widows, the women who managed family affairs while their husbands were away at sea.

🍁 🍁 🍁

Illustrations

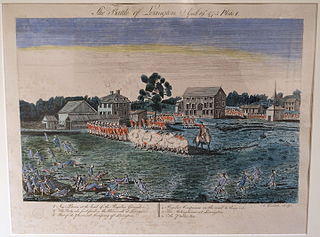

Battle of Lexington by Amos Doolittle.

Summons to Provincial Congress.

Thirkleby Hall, 1800.

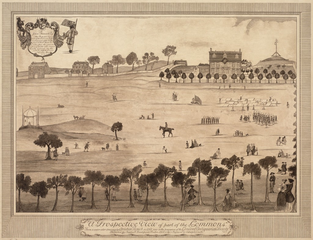

Boston Common.

Clark-Frankland House, Boston.

Death of General Warren at the Battle of Bunker Hill by John Trumbull.

Dateline — Battle of Bunker Hill, June 17, 1775.

Journals of Each Provincial Congress of Massachusetts in 1774 and 1775.

“The Story of Agnes Surriage, the Marblehead Tavern Maid.” Historic Ipswitch.

“Agnes Surriage, Lady Frankland.” Britannica.

Sira Dooley Fairchild. “Finding Lady Frankland.” Boston History.

“Agnes Surriage and her Journey from Tavern Wench to Lady of the Manor.” New England Historical Society.

“Sir Harry.” Ashland Historical Society.

F. Marshall Bauer. Marblehead’s Pygmalion: Finding the Real Agnes Surriage. 2010.

Sandra Wagner-Wright holds the doctoral degree in history and taught women’s and global history at the University of Hawai`i. Sandra travels for her research, most recently to Salem, Massachusetts, the setting of her new Salem Stories series. She also enjoys traveling for new experiences. Recent trips include Antarctica and a river cruise on the Rhine from Amsterdam to Basel.

Sandra particularly likes writing about strong women who make a difference. She lives in Hilo, Hawai`i with her family and writes a blog relating to history, travel, and the idiosyncrasies of life.

Nice! You always teach me something new.

Great history!