Research can turn up fascinating stories that aren’t directly related to the topic being investigated. Last October, I shared the story of Lady Agnes Frankland, the poor girl from Marblehead, Massachusetts who married an English Aristocrat.

Last week while transcribing research notes I gathered at the Phillips Library, I met Eliza Burditt whose ill-fated romance probably started on a vessel much like the one on the left. Her subsequent tale of woe is not unique. Nor is her situation entirely clear. Yet I take this opportunity to extract Eliza from the flotsam of generally unknown correspondence.

Voyages of the Telemachus

In 1812 Eliza wrote three letters to John Crowninshield; he responded to two of them. The desperate young woman wrote John because the Salem merchant owned the brig Telemachus, and had employed David Burditt as First Mate on the vessel. In search of new trading opportunities at a time when American traders had to avoid capture by either French or British privateers, John Crowninshield sent the Telemachus and her sister ship Dido to Archangel in Russia.

Upon their arrival in June 1810, Capt. Townsend, leader of the expedition, realized other traders had the same idea, and the trade goods he had to offer, all luxury items, were a glut on the market. The Telemachus and Dido carried currants, raisins, pepper, sugar, coffee, cassia, nutmegs, cloves, frankincense, and oil. But the pepper didn’t sell well. The coffee quality was too poor for the market. Happily, sugar did well, but the oil was a total loss, because its sale was prohibited by local authorities. Such were the vagaries of international trade.

Capt. Townsend decided to wait in Archangel until winter before unloading the cargo from both vessels onto sledges and taking them to Moscow where the market was better. Townsend went with his goods, and sent the Telemachus back to Salem under David Burditt’s command with a cargo of iron and hemp.

Burditt first sailed to Bordeaux, a French port in southwestern France where he hoped to pick up French products such as brandy and ladies kid gloves. He arrived in January 1811, and waited. Like many transient merchants and ships’ officers, Burditt took rooms at a boarding house run be Mdm. Beauvais. John Crowninshield lived there during the years 1803-1806 when he managed his family’s European trade. Eliza’s father, a Mr Emery, was a frequent visitor at the time. Whether Mr. Emery still frequented Mdm. Beauvais’ house when David Burditt resided there is unknown.

French authorities required extensive paperwork before a cargo could be acquired, including direct approval from Paris before any outbound cargo cleared. And, the price of brandy was high. Despite the setbacks, in June the Telemachus was ready to depart with a cargo of brandy and silk. Burditt also accepted passengers. Two of these were Eliza Emery and her sister who booked passage to America. It proved to be a short voyage.

Just outside of Bordeaux, British privateers captured the Telemachus and escorted the vessel to the Isle of Guernsey where the Admiralty Court condemned both ship and cargo for illegally stopping at a French port. David Burditt and other crew members booked passage to New York City. It appears Eliza and her sister traveled on the same vessel. [Painting of John Crispo beside a depiction of the French cutter Telemachus.]

A Romance

It appears that David Burditt paid special attention to Eliza and her sister, both while he awaited the Admiralty Court’s ruling and on the voyage to America. Eliza confided to John Crowninshield that because Burditt had been such an attentive good friend to her, she concluded he would be a good husband. Eliza said she and David married, and all was well, and he said he would take her to Salem to meet his family. But on October 17th he left her in New York and went to Salem without his wife.

Did Eliza question her husband’s decision? Did she wonder why he didn’t take her to meet his family? Since he would have just received his wages for his service on the Telemachus, he should have had sufficient funds. It appears that Burditt left Eliza with some funds and kept in contact until February 1812. And then, nothing.

Eliza ran out of funds, and sold her watch. She was outraged by her husband’s neglect. Yet, she kept hoping Burditt would contact her. At the end of May, Eliza Burditt was more distraught than angry . Had something happened to her husband? Was there something he hadn’t told her? Desperate, Eliza wrote her first letter to John Crowninshield.

“Something must have happened to him,” she wrote, “I cannot imagine he would be capable to leave me so long in a strange place.”

to be continued . . .

⛵️ ⛵️ ⛵️

Illustrations

Painting of Schooner James M. Waterbury by Elisha Taylor Baker. About 1890.

Archangel, Russia. 1900.

Port of Bordeaux by Joseph Vernet. 1758.

Portrait of Cmdr. John Crispo beside a depiction of the French cutter Telemachus. About 1797.

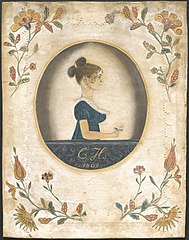

Woman Holding a Rose. 1809.

Eliza Burditts to John Crowninshield May 29, 1812, June 5 1812, August 4, 1812. Box 5, Folder 3. John Crowninshield Non-Family Correspondence 1806-1812. Phillips Library, Peabody Essex Museum.

John Crowninshield to Eliza Burditts June 5, 1812, August 10, 1812. Ibid.

John H. Reinoehl. “Post-Embargo Trade and Merchant Prosperity: Experiences of the Crowninshield Family 1809-1812.” Mississippi Valley Historical Review. Vol. 42. No. 2. 1955.

Sandra Wagner-Wright holds the doctoral degree in history and taught women’s and global history at the University of Hawai`i. Sandra travels for her research, most recently to Salem, Massachusetts, the setting of her new Salem Stories series. She also enjoys traveling for new experiences. Recent trips include Antarctica and a river cruise on the Rhine from Amsterdam to Basel.

Sandra particularly likes writing about strong women who make a difference. She lives in Hilo, Hawai`i with her family and writes a blog relating to history, travel, and the idiosyncrasies of life.