For various reasons, we are more aware of some First Ladies than others. Last week, I skipped over Edith Roosevelt and Helen Taft in favor of closing the blog with Edith Wilson. This week, I intended to begin with Lou Hoover, but I started thinking about 1920 as a pivotal year.

The United States had emerged from World War I without ratifying the 1919 Versailles Treaty with its stipulation for a League of Nations. Woodrow Wilson’s international agenda was in tatters. Due to President Wilson’s illness, the White House was a closed monument. In 1920, Americans were ready for a change. The American economy, though in a post-war recession, would soon boom. American women had the right to vote. Anything seemed possible. Would the office of First Lady reflect these changes?

Florence Kling Harding

As a teenager in Marion, Ohio, Florence worked in her father’s hardware store where she clerked, kept the books, and even rode her horse to collect rent from farmers working land owned by her father.

In 1880, independently minded Florence eloped with Pete DeWolfe in what may have been a common law marriage. The couple had a son before DeWolfe left his family in 1882. Four years later Florence divorced her husband, a bold move in 1886. In later years when Florence’s second husband, Warren Harding, entered politics, Florence encouraged the press to assume her first marriage ended in widowhood, a more respectable status than divorcee.

In 1891, Florence married Warren Harding, owner of the Marion Star. During the course of their marriage, Harding called his wife “The Boss,” and she referred to her husband as “Sonny.” Harding was five years younger than his wife.

In 1894 Florence became the business manager of her husband’s paper. Though she didn’t write articles, Florence hired the paper’s first woman reporter, recruited newsboys to deliver the paper, and subscribed to a news wire service that brought her Marion, Ohio readers global news with 24 hours.

Florence supported her husband’s political career, even selecting his clothing, as he rose in state politics. In 1905, Florence took time off to recuperate from emergency surgery for nephritis. While she convalesced in the hospital, Harding began an affair with a close friend. Though he promised to end it, the affair continued.

Harding became a U.S. Senator in 1914, and the family moved to Washington D.C. In 1920, Harding ran for president from their home in Marian via what was called a Front Porch Campaign. The venue allowed Florence to control who met with her husband, and also to embark on her own campaign to prove Harding understood people’s concerns. For example, one day she might wear an apron while she pared apples with farmer’s wives – a play for the traditional female vote. Another day, Florence explained she didn’t wear a wedding ring because it symbolized bondage – an effort to reach educated female reformers.

Voters elected Harding, and turned away from progressive, international politics. An anecdotal conversation between the new president and his wife after his first address to the Senate illustrates their partnership.

Florence asks: “Well, Warren Harding, I have got you the presidency. What are you going to do with it?”

To which he replies: “May God help me, for I need it.”

With his wife’s approval, Warren Harding opened the White House to the public. On many occasions, Florence personally acted as tour guide. In response to a mild economic depression in 1921, Florence set an example of economizing measures at the White House. She shut off exterior water fountains and any rooms not in use. But she continued to entertain, often inviting several thousand guests. Florence and her husband also held poker parties in the White House Library where they ignored Prohibition and served liquor.

In 1923 the Hardings embarked on a cross-country tour, including the territory of Alaska. The president became ill and was rushed to San Francisco where he died of a heart-related illness on August 2, 1923. A year later, Florence died from renal failure.

Grace Coolidge

The Coolidges were on vacation in Vermont when they learned of the president’s death, Grace Coolidge held a kerosene lamp while her father-in-law, a notary public, administered the oath of office to her husband.

Grace was a popular White House hostess, but she wasn’t privy to her husband’s work or plans. When Coolidge decided not to run for re-election in 1928, he announced his decision to the press before mentioned it to her.

Lou Henry Hoover

Lou Hoover was well-educated, well-traveled, and accustomed to working for public causes. She met her husband when she was a first year geology student at Stanford University, and he was a senior. She finished her degree while Hoover went to Australia as a mining engineer in the gold mines. As soon as she graduated, Hoover cabled Lou a marriage proposal – which she accepted by return cable.

After the marriage ceremony, the Hoovers sailed for Shanghai where Hoover worked for the Department of Mines. Lou learned Mandarin Chinese, and in later years the couple spoke in Mandarin if they wanted to have a private conversation in a pubilc place. The Hoovers were in Tientsin, China during the 1900 Boxer Rebellion. Lou helped build barricades, and served her shifts of guard duty.

When World War I broke out in 1914, the Hoovers were in London where Herbert Hoover had founded his own firm. Lou chaired the American Women’s War Relief Fund and Hospital to raise immediate funds for refugees. At the request of the American ambassador, Lou also led the Commission for Relief in Belgium.

When the U. S. entered the war in 1917, President Wilson named Hoover as chief of the Food Administration. Lou’s Hoovering Guidelines, which included recipes, publicized how Americans could conserve food by going one day without meat, and another without wheat.

From 1921 to 1928, Hoover served as Commercy Secretary. Lou became active during the founding years of the Girls Scouts of America, supported other women’s organizations, and engaged in public lectures.

When she became First Lady in March 1929, Lou curtailed her public activities, but continued official entertainments, one of which was a series of teas for congressional spouses. The representative from Chicago, Oscar Stanton DePriest, was the first African American elected to Congress in the 20th century. In order to treat congressional wives equally, Lou decided to hold 5 separate teas and invited Jessie DePriest to the final tea on June 12, 1929.

There was an immediate backlash from segregationists, including formal votes in the state legislatures of Texas, Florida, and Georgia to censure Lou Hoover. The First Lady didn’t respond to their criticism.

The greatest single event to affect the Hoover Administration was the Stock Market Crash of 1929, followed by what would become the Great Depression. Lou Hoover’s most notable response was to organize a volunteer effort, encouraging Girl Scouts to see who was struggling in their respective communities, and make plans for sending relief where it was most needed.

Lou responded to threats to the cotton textile industry by wearing a cotton evening gown, rather than silk, to a White House reception. The Hoovers also decided they would personally fund White House entertainments, but never publicized their contributions, thus giving the impression that while Americans suffered food shortages, presidential life was untouched by the crisis.

~ * ~

Illustrations

President Coolidge with members of American Chemical Society on White House Lawn, 1924. Scaffolding shows White House again under repair.

Warren and Florence Harding in their garden.

Mrs. Harding and the Girl Scouts, 1922.

Warren and Florence Harding at the White House, c.1921

Portrait of Florence Harding, 1923.

Portrait of Grace Coolidge, 1926.

Lou Hoover in Tientsin, China, c.1900.

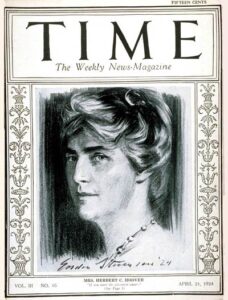

Lou Hoover on cover of Time Magazine, 1924.

Jessie DePriest. Photo by Addison N Scurlock, 1929.

Portrait of Lou Hoover by Richard Marsden Brown, 1950.

National Museum of American History: First Ladies

First Ladies of the United States. National Portrait Gallery

Sandra Wagner-Wright holds the doctoral degree in history and taught women’s and global history at the University of Hawai`i. Sandra travels for her research, most recently to Salem, Massachusetts, the setting of her new Salem Stories series. She also enjoys traveling for new experiences. Recent trips include Antarctica and a river cruise on the Rhine from Amsterdam to Basel.

Sandra particularly likes writing about strong women who make a difference. She lives in Hilo, Hawai`i with her family and writes a blog relating to history, travel, and the idiosyncrasies of life.