I grew up in a different America, one that had one black plastic rotary phone per household and one black & white family television powered by tubes. Yes, it was that long ago. Christmas trees were “live” with scraggly branches and decorated with strands of tinsel that had to be correctly placed, usually by a child. Printed holiday greetings were restricted to: Merry Christmas, Happy Hanukkah, and the neutral Seasons Greetings.

The cheerful holiday cards were supposed to be a pleasant way to wish friends and colleagues a happy holiday season. Businesses also utilized the cards so customers had a more personal connection to the firm, like this 1957 card from First National Bank. Note “Visit Us” in the upper right-hand corner.

Cards are more convenient than letters

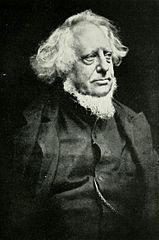

Sir Henry Cole, founder of the Victoria & Albert Museum, came up with the idea of a commercial Christmas greeting card in 1843, because he received too many Christmas letters. Among those who could afford the postage, it was customary to exchange Christmas letters. Recipients paid for the postage upon receipt, depending on the number of letter sheets and the distance the letter traveled. In 1840 a new postage system came into effect. A self-adhesive one-penny stamp paid for by the sender allowed letters up to half-an-ounce, regardless of the distance traveled. Suddenly, members of the middle class could easily send affordable Christmas letters.

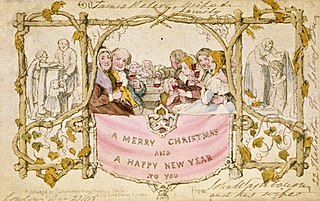

This might seem like a clever holiday custom. Cole didn’t see it that way, because every Christmas greeting had to be answered, and he didn’t have time to write all those letters. So, he went to an artist he knew, J. C. Horsely, and asked him to sketch a portrait of a family enjoying Christmas dinner. On either side of the main picture were sketches of people helping the poor. At the bottom, the holiday greeting read: Merry Christmas and Happy New Year. Cole printed 1,000 copies of the drawing on stiff cardboard and sent a card to everyone who mailed him a greeting. He then sold leftover cards for 1 shilling each.

There was one problem that prevented the new custom from immediately taking off. The feasting family was drinking red wine – even the children. Victorian England had a strong Temperance Movement, and such pictures weren’t received well.

About 30 of the cards have survived, and if you would like one of them, Christie’s Auction House in London has one for sale. They expect the buyer to pay between £5-8,000. Or you might find one at Getman’s Virtual Bibliophilic Holiday Gift Fair Dec. 4-7, 2020.

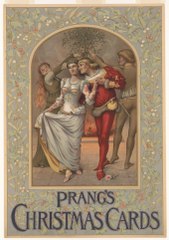

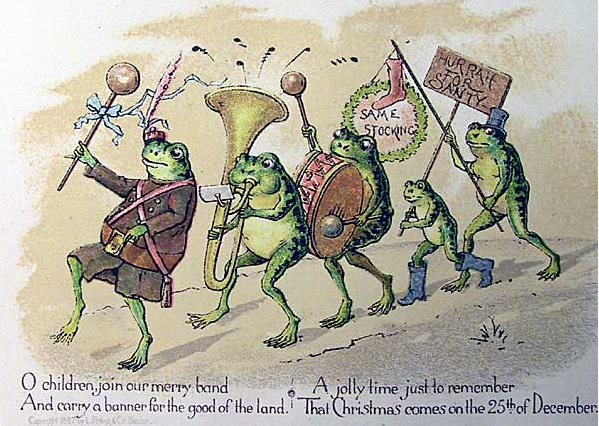

The American Christmas card custom began in 1875 when Louis Prang, a Boston printer, published a postcard with a painting of a flower and a Merry Christmas message. Prang’s themes were based fanciful animals and plants. The novelty cards caught on – within 10 years, Prang sold 5 million cards each year.

The modern Christmas card industry began in 1915 when Hallmark Cards developed a card that folded in the middle and could be placed in an envelope. The message could be longer and more private than a post card without being a full-length letter.

Christmas cards can be an annual burden

Sending annual Christmas cards to friends and family near and far became a ritual of torment and delight. Many of the recipients hadn’t seen each other in years, so writing a chatty note about family and personal news was of prime importance. To send a card without a note was as much of an affront to the recipient as failing to send a card at all. But for the sender, this social requirement could be a tedious experience, especially if everyone else’s children seemed to be doing so much better than yours.

At our house, my parents wrote cards at the last possible moment so they reached their destination before Christmas. Boxes of cards sat on the dining table for at least two weeks, before each parent bit the bullet and set about doing their allotted cards. As a child, I couldn’t help but wonder why they did such an unpleasant ritual.

When cards arrived, they were scrutinized. “Louis got a promotion,” my mother would say, looking at my father. Ouch! The cards were always attractive, and became part of our holiday decor, hung over strings stretched across the wall above the fireplace. After the holiday, the cards were usually discarded, sometimes directly into the fire.

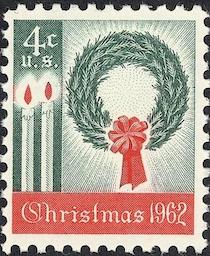

In the early 1950s, a postage stamp cost 3 cents. Ten years later, the rate had increased to 4 cents. Boxes of 25-30 cards didn’t cost much either. Even the annual letter could be streamlined. Some folks typed their letters on mimeograph stencils and produced them on the machine. Later, copiers allowed people to use special paper and add designs without getting purple ink on their fingers.

As time moved on, the inveterate card-senders of my parents’ generation had fewer folks to update on family happenings. Fashion moved to photo cards with a family portrait or photo of the children in front of the Christmas tree. Senders could get away with a short note, rather than a letter. Postage rates went up. In 1973, a postage stamp costs 8 cents; in 1993 a stamp costs 53 cents, and in 2013 the cost was 46 cents. Greeting cards also became more expensive, pushing into a $5.00 price tag for a fancy individual card. And then, of course, social media and ecards appeared.

Facebook friends send family updates and photos on a frequent basis. Ecards are timely, don’t require long messages, and can do all sorts of things a static paper card can’t, for example, animated reindeer flying over rooftops or nuns singing Hallelujah.

Ecards are convenient: both easy to send and fun to receive, but … the personal touch and effort that goes into selecting and sending cards to special friends and family keeps the greeting card industry afloat. Millennials, in particular, like to purchase specialty cards. In today’s holiday customs, greetings are convenient again, without the burden of an annual letter.

Illustrations

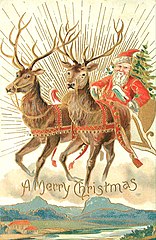

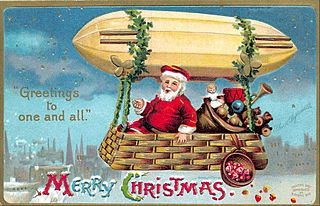

Christmas Postcard 1907

First National Bank Christmas Card 1957

Sir Henry Cole

First Christmas Card, designed for Henry Cole, 1843

Two Cards by Louis Prang: Renaissance Couple & Marching Frogs

1962 Christmas Stamp

Santa Postcard 1909

Getman’s Virtual Bibliophilic Holiday Gift Fair.

Janhvi Bhojwani. “Greeting Cards are Still a Thing in the Digital Age. NPR. Feb 14, 2019.

John Hanc. “History of the Christmas Card.” Smithsonian Magazine. Dec. 9, 2015

William J. Kole. “Cheers! Or not: ‘Scandalous’ 1st Christmas Card up for Sale.” AP News. Dec. 2, 2020.

Sandra Wagner-Wright holds the doctoral degree in history and taught women’s and global history at the University of Hawai`i. Sandra travels for her research, most recently to Salem, Massachusetts, the setting of her new Salem Stories series. She also enjoys traveling for new experiences. Recent trips include Antarctica and a river cruise on the Rhine from Amsterdam to Basel.

Sandra particularly likes writing about strong women who make a difference. She lives in Hilo, Hawai`i with her family and writes a blog relating to history, travel, and the idiosyncrasies of life.

Your parents’ annual struggle made me laugh in sympathy and recognition. Also amused to know Christmas cards have their roots in pragmatism and base commercial motives:). Receive mercifully few cards these days (moving continents no doubt helped), none of them perfunctory, and I enjoy painting watercolour or doing intricate calligraphy cards in response. Fascinating blog, as ever Sandra, thank you.

Hi Toni — So glad you enjoy the blogs. I like your idea of designing your own cards. Alas, I lack both talent and patience for card designs. Enjoy the holidays.

Hi Sandra,

Now checking in on your blogs, nice to hear about some of what some normal living in the US was, very good, I appreciate this! Being an immigrant, we did not have a phone until I was 13 yrs old and the tv we had in Sydney was stolen, so no more tv until we got to the us. So interesting to read how people felt about cards and such. We always just enjoyed receiving them and sending them. It is nice to stay connected with those so far away. I still enjoy sending cards (yes, do ecards too) it makes me remember our times together and all. Thank you Sandra, very much for your blogs. Paula

Paula, thanks for sharing a different and important perspective.