Rotunda, National Museum of Natural History

On August 10, 1846 President James K. Polk, a man little remembered today, signed The Smithsonian Institution Act to create what we generally generally think of as our national museum. But Polk’s action was neither the beginning nor the ending of the story I’m about to tell.

The story begins in 1688 with the birth of Philadelphia Revely. Her father was a Squire in Newby Wisk, Yorkshire. Nothing remarkable there. She married Langdale Smithson, the second son of Sir Hugh Smithson, Baronet of Stanwick, Yorkshire. Yawn. About 1700, Philadelphia produced a son, Hugh, who eventually gained his grandfather’s title.

Matters become more interesting in 1740 when Sir Hugh Smithson married Elizabeth Seymour, Baroness Percy. From his perspective, he married up. She on the other hand, became mere Lady Betty Smithson. But the wheel of fortune turned. Betty’s father became the 7th Earl of Somerset and the 1st Earl of Northumbria. Because he had no legitimate heirs, the Northumbrian title and landholdings would pass to his son-in-law Hugh Smithson, and then to his legitimate heirs from his marriage to Betty. In 1750 by Act of Parliament, Hugh Smithson became Hugh Percy, Duke of Northumberland.

1st Duke of Northumberland

Hugh and Betty had two sons and a daughter. Hugh, however had at least one other son with his longtime mistress, Elizabeth Hungerford Keate Macie, one of his wife’s cousins.

Elizabeth

In 1719, Elizabeth married John Macie of Bath who became the High Sheriff of Bath in 1753. After Macie died in 1761, Elizabeth married John Marsh Dickinson, by whom she had a son. Elizabeth also began a long relationship with Hugh Percy, the Duke of Northumberland. Just coming to the important bit.

About 1765, Elizabeth became pregnant, and when she could no longer conceal her situation, she moved to Paris where she gave birth to James Lewis Macie, later Smithson. As an illegitimate, and presumably unacknowledged, son young James did not share his father’s surname. Nor could he have a career in the army, church, civil service, or politics. But he could attend university.

So, James attended Pembroke College at Oxford, and began a scientific career. In 1787 he became a Fellow of the Royal Society. He published his first scientific paper in 1790 on the chemical properties of tabasheer, a substance found in bamboo. During his lifetime, James wrote two hundred papers, with twenty-seven reaching publication. The papers discussed, among other topics, an improved method of producing coffee, and an analysis of the mineral calamine, an important component in producing brass. In honor of this discovery, the mineral was later called smithsonite. When he wasn’t writing scientific papers, James gambled.

In 1801, after his mother’s death the previous year, James changed his surname to Smithson. Elizabeth left her considerable fortune to her two sons, James and his half-brother.

James never married, or had any known children. On June 27, 1829 James Smithson died in Genoa Italy, and was interred in the English Cemetery in a plot purchased by his nephew, Henry Hungerford.

The Bequest

James left his entire fortune to his nephew, but stipulated that if his nephew died without heirs, his entire estate would go to the United States with the stipulation that the funds be used to found an institution for the increase and diffusion of knowledge. The new institution would be called The Smithsonian Institution.

In 1835 Henry Hungerford died without heirs. The following year, Congress accepted Smithson’s bequest and sent Richard Rush to England to retrieve it. Rush returned with eleven boxes, containing 104,960 sovereigns, eight shillings, and seven pence. When the gold was melted down, it was valued at over $500,000 [the equivalent of over $12 million in 2019]. Rush also brought back Smith’s mineral collection, library, scientific notes, and personal effects.

Congress invested the funds in U.S. Treasury bonds issued by the State of Arkansas. [At the time the United States had no central bank.] Arkansas defaulted, and lost the funds. John Quincy Adams, Congressman from Massachusetts, convinced Congress to replace the funds. Eight years after receiving the bequest, Congress decided to create a museum, library, and a program of research, publications, and collections in the sciences, arts, and history in the new Smithsonian Institution. President Polk signed the bill on August 10, 1846. Construction began in 1849 on a building still known as “The Castle, which opened in 1855.

But wait, there’s more

In 1891, Samuel P. Langley, secretary of The Smithsonian Institution, decided that the Institution had an obligation to maintain Smithson’s grave in Genoa. He deposited £30 with the treasurers of the British Burial Ground to maintain Smithson’s tomb.

Ten years later, the British Consul informed the Institution’s regents that by 1905 Smithson’s grave would be relocated. Regent Alexander Graham Bell urged the regents to bring Smithson’s remains to the Institution he had founded. The regents debated for two years, and in 1903 authorized Bell to exhume and transport Smithson’s remains. Bell and his wife arrived in Genoa on Christmas Day 1903. During a storm on the December 31st, Bell supervised the exhumation.

On January 7, 1904, just before Smithson’s casket was sealed, Bell deposited a wreath made from the leaves of a tree that stood next to the Genoa grave, a poetic touch Smithson would probably have appreciated.

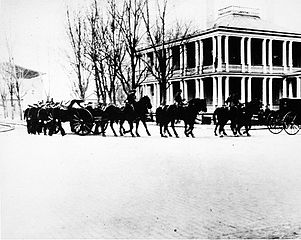

It took two weeks for the German ship Princess Irene to make the crossing to New York. President Teddy Roosevelt ordered the USS Dolphin to escort the ship to Hoboken, New Jersey, where Smithson’s casket was transferred to the Dolphin for the voyage to the Washington Navy Yard. After a brief ceremony at the dock on January 25th, the caisson carrying Smithson’s coffin was escorted through southwest Washington by the U. S. Calvary. Smithson’s remains were taken to the Regents’ Room at the Institution where Smithson’s personal effects had been on display since 1880.

Apparently, the display lacked something. In November 1904 Institution personnel returned to the British Cemetery to pack Smithson’s sarcophagus into sixteen crates which were shipped to New York aboard the Princess Irene. On March 6, 1905, Smithson’s remains were removed from the Regents’ Room and placed into a sealed vault beneath Smithson’s monument.

Today The Smithsonian Institution is 174 years old, the world’s largest museum, education, and research complex. It includes seventeen museums and galleries, the National Zoo, and the Smithsonian Gardens. The museum collection has more than 150 million objects, many of them accessible, but not on public display. A sample of some of the specimens in the Museum of Natural History is in the video below. [Don’t be put off by the black & white opening.]

James Smithson could never have imagined the Institution he founded, and how well it fulfills his mandate to increase and diffuse knowledge.

🏛🏛🏛

Illustrations

Rotunda, National Museum of Natural History by James DeLoreto, Smithsonian, 2015.

Elizabeth Percy by Joshua Reynolds.

Hugh Percy, 1st Duke of Northumberland.

James Macie Smithson at Oxford.

James Smithson, 1816.

The Castle, Smithsonian Institute.

Cortege with Smithson’s Remains, 1904.

Crypt of James Smithson, 1905.

“Mr. Smithson Goes to Washington.” Smithsonian Preservation Quarterly. Summer/Fall 1995.

The Philadelphia Revely Commonplace Book.

Michael Farquhar. “James Smithson.” Washington Post. Jan. 10, 1996.

Sandra Wagner-Wright holds the doctoral degree in history and taught women’s and global history at the University of Hawai`i. Sandra travels for her research, most recently to Salem, Massachusetts, the setting of her new Salem Stories series. She also enjoys traveling for new experiences. Recent trips include Antarctica and a river cruise on the Rhine from Amsterdam to Basel.

Sandra particularly likes writing about strong women who make a difference. She lives in Hilo, Hawai`i with her family and writes a blog relating to history, travel, and the idiosyncrasies of life.