Victoria Woodhull was the first woman to address a Congressional Committee and the first woman to run for president. She and her sister were known as spiritualists as well as being the first women to own a newspaper and a stock brokerage. But Victoria Woodhull’s most notorious reputation was her advocacy for free love. Thomas Nast, prolific illustrator, pilloried Victoria as [Mrs.] Satan incarnate because she rejected marriage as an oppressive institution and embraced what she termed sexual freedom.

In the foreground, the viewer sees Victoria wearing her black wings and carrying the banner for Free Love. In the background, the virtuous wife carries her alcoholic husband and her children on the treacherous path of life. The caption beneath reads: “Get Thee Behind Me, [Mrs. Satan]! I’d rather travel the hardest path of matrimony than follow in your footsteps.”

[Details about Victoria Woodhull’s early career may be found here.]

The Vanderbilt Connection

Thomas Nast’s visual rejection was less harmful to Victoria Woodhull and her sister Tennesee Clafflin than the loss of Cornelius Vanderbilt’s goodwill. Cornelius Vanderbilt was one of America’s earliest self-made millionaires. During late 1860s, Vanderbilt became interested in spiritualism and the expertise Victoria Woodhull and her sister Tennessee Claflin provided. Some say Tennesee provided more than spiritual services, and after the death of Vanderbilt’s wife, Tennessee became a regular visitor to Vanderbilt’s home and office. Coincidentally, Vanderbilt provided the financing for Woodhull & Claflin’s brokerage and newspaper.

In 1869 Vanderbilt married Frank Crawford Vanderbilt, a cousin Vanderbilt and his first wife had in common. Frank signed a prenuptial agreement that provided her with $500,000 in bonds at the time of her husband’s death. Frank did not approve of the continued relationship her husband had with Victoria and Tenneseee. In 1871, both sisters were denied access to Vanderbilt’s home, and he ceased to send funds to the sisters.

In May 1871 an interfamily lawsuit brought Tennessee to a New York witness stand where she declared: “I am a clairvoyant; I am a spiritualist; I have power and I know my power,…Many of the best men in the street know my power. Commodore Vanderbilt knows my power. I have humbugged people, I know. But if I did it, it was to make money …” [Well, if that’s all it was…]

In February 1872, the same month Nast published “Mrs. Satan,” Victoria delivered a speech criticizing Vanderbilt and other railroad magnates as betrayers of the public trust. Victoria broke the Beecher-Tilton story the same month and in November found herself in the Ludlow Street Jail.

After six months and paying $500,000 in bail and fines, Victoria, her sister Tennessee, and her husband Col. Blood were acquited of all charges.

Funds for a Fresh Start

Essentially destitute, Victoria and her sister tried to restart their newspaper and in 1875 they published an open letter to Cornelius Vanderbilt. “We want our paper endowed beyond fear of disaster . . . [This] would require a paltry sum only when compared to your many millions – a sum whose absence neigher you nor your heirs would scarcely feel; but which for what we ask, it would be salvation indeed.” Vanderbilt did not reply.

[In an unrelated matter, Victoria divorced Col. Blood.]

On January 4, 1877, Cornelius Vanderbilt died, leaving an estate valued at $105 million. Vanderbilt left eleven surviving children: two sons and nine daughters. The eldest son, William, and his sons received 95 percent of the estate. William’s brother and two of his sisters sued, claiming that Vanderbilt was not in his right mind when he made the will. William settled the suit out of court by giving his brother and each of the two sisters who complained $200,000 and a trust fund of $400,000.

Prior to the settlement and worried the sisters might testify on behalf of his siblings, William paid Victoria and Tennessee $1000 to leave the country. The sisters relocated to England where Victoria returned to the lecture circuit.

Victoria Woodhull Martin

On December 4, 1877 Victoria gave a lecture on “The Human Body, The Temple of God” at St. James Hall in London. In the audience, banker John Biddulph Martin fell under Victoria’s spell. The couple married on October 31, 1883. Victoria continued to lecture and also published a magazine, The Humanitarian, which emphasized eugenics as a means of social progress.

Victoria and her husband put Victoria’s controversial American past behind them. Victoria was, apparently, misunderstood. “Free love is not what I asked for nor what I pleaded for. What I asked for was educated love, that our daughters be taught to love rightly.”

In 1894, Victoria and her husband sued the British Museum for libel, because the museum exhibited pamphlets related to the Beecher-Tilton Scandal. They said the pamphlets incriminated Victoria with information that was false. They lost the case, but proved they would not allow Victoria’s reputation to be tarnished.

When Martin died in 1901, Victoria and her sister moved to Bredon’s Nortan, a small village near Worcestershire where they began a life of good works, including a donation of £55 for church renovations, gas street lights, a postal service, and telephone availability.

Victoria also became active in the Sulgrave Movement, an effort to improve relations between the United States and England. Victoria contributed funds to purchase Sulgrave Manor, the home of George Washingtons’ ancestors, located in Northamptonshire, England. [In this photo, the right side of the structure is the original 16th century manor house.]

In her later years, Victoria enjoyed ‘motor cars’ and dismissed numerous chauffeurs, because they didn’t drive fast enough. Finally, Victoria took her place behind the wheel of her Mercedes Simplex. In 1903, Victoria was the first woman observed driving a motor car in Hyde Park, London. The following year, she founded a Lady’s Motor Club.

Victoria Woodhull died on June 9, 1927. There is a cenotaph in her honor at Tewkesbury Abbey in Worcestershire. In 2001, Victoria was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame in Seneca Falls NY.

🌠 🌠 🌠

Illustrations

Thomas Nast. Mrs. Satan. Harper’s Weekly, Feb. 17, 1872.

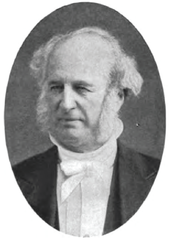

Cornelius Vanderbilt.

Frank Armstrong Crawford Vanderbilt. 1906.

Victoria Woodhull, 1880.

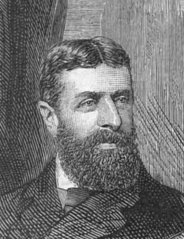

John Biddulph Martin, 1886.

Lane in Bredon’s Norton. Attribution: Lane in Bredon’s Norton by Peter Whatley.

Photo of Sulgrave Manor. Attribution: Cathy Cox.

Photo of Mercedes Simplex 40 PS by Triple-green.

Edward Renehan.”Strange Bedfellows: Commodore Vanderbilt and the Woodhull/Claflins.” History News Network. Dec. 2, 2007.

Sulgrave Manor, Ancestral Home of George Washington.

Sandra Wagner-Wright holds the doctoral degree in history and taught women’s and global history at the University of Hawai`i. Sandra travels for her research, most recently to Salem, Massachusetts, the setting of her new Salem Stories series. She also enjoys traveling for new experiences. Recent trips include Antarctica and a river cruise on the Rhine from Amsterdam to Basel.

Sandra particularly likes writing about strong women who make a difference. She lives in Hilo, Hawai`i with her family and writes a blog relating to history, travel, and the idiosyncrasies of life.