On Sept. 14, 1814 Francis Scott Key jotted down the poem that became the American National Anthem. The United States was engaged in its second war against Great Britain, and events weren’t going well.

The war, which some call the Second American Revolution, was about trade and citizenship — two issues that are still controversial.

America’s war was part of a larger struggle between Britain and Napoleonic France. Each side wanted to starve the other out by restricting trade to the enemy. The United States wanted to trade with everyone and declared that whichever nation stopped restricting American trade would receive exclusive trade from the United States.

In 1810, Napoleon indicated that he would lift the restrictions. President James Madison blocked all trade with Britain.

Meanwhile, Americans on the western frontier faced increasing hostility from Native Americans. The British, Americans believed, were supplying weapons to Native Americans.

Lastly, the citizenship issue. The British didn’t allow anyone to reliquish birth citizenship and give allegiance another country. The British also needed men to serve in the navy. They began stopping American ships and impressing members of the American crew into British naval service.

Taking these provocations into consideration as well as the possibility of annexing Canada to the United States, Congressional War Hawks finally pressured President Madison to sign a declaration of war.

United States troops immediately attacked Canada, a British colony, and were repulsed.

In July 1813 Baltimore and Ft. McHenry were likely targets for a British attack. Major George Armistead, commander at Ft. McHenry informed the officer in charge of Baltimore defenses that he needed a large flag, allegedly saying, “We, sir, are ready at Fort McHenry to defend Baltimore against invading by the enemy…except that we have no suitable ensign to display over the Star Fort, and it is my desire to have a flag so large that the British will have no difficulty in seeing it from a distance.”

The job of producing the flag went to professional flag maker Mary Young Pickersgill. She engaged her daughter, three nieces, a young indentured servant, and (some suggest) her mother to produce a garrison flag 30 feet by 42 feet. Each star in the 15-star flag measured two feet in diameter.

Materials included 300 yards of English wool bunting and cotton for the stars. Working ten-hour days, the seamstresses delivered the flag August 19, 1813. The flag was so large, it took eleven men to hoist it to the top of the flag pole. Armistead paid Mary $405.90 [now about $8,089.23]. Mary and her team also made a smaller 17 feet by 25 feet storm flag for a fee of $168.54 [now about $3,358.85].

Francis Scott Key was an American lawyer. One of his friends, Dr. William Beannes, was a prisoner on a British ship near Baltimore. Key successfully negotiated his friend’s release and returned with him to a nearby American vessel. The British detained the American ship eight miles away from Ft. McHenry to prevent any warning of the imminent British attack.

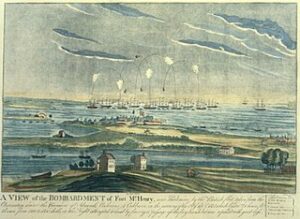

On Sept. 13, the British commenced their bombardment of Ft. McHenry. “It seemed,” Key later wrote, “as though mother earth had opened and was vomiting shot and shell in a sheet of fire and brimstone.” Five British ships began lobbing 190-pound shells into the fort as well as rockets with exploding war heads. The attack continued throughout the night for a total of 25 hours. The British fired 133 tons of shells.

Throughout the night, Key watched, occasionally catching glimpses of the flag. At daybreak, he saw it still flew above the fort. Key wrote a four stanza poem “The Defence of Fort McHenry.” The British halted their attack and sailed away.

In fact, the garrison flag didn’t fly through the night. In addition to the bombardment, there was a rain storm. The garrison flag, when wet, would weigh 500 pounds and snap the flagpole. Probably, the garrison flew the storm flag through the night and hoisted the garrison flag in the morning.

Key’s poem circulated first as a handbill, and was then printed in newspapers. The words were set to music, a popular English drinking song called “To Anacreaon in Heaven.” People called the new song “Star-Spangled Banner,” and added it to two other popular patriotic songs: “Hail Columbia” and “Yankee Doodle.” During the Civil War, the Star-Spangled Banner became the anthem for Union troops, replacing other songs.

In 1916, President Wilson declared that the Star-Spangled Banner would be played at all official events. On Mar. 3, 1931 Congress adopted the Star-Spangled Banner as the official national anthem.

What happened to the Ft. McHenry flag?

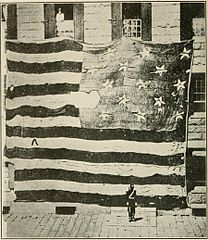

Armistead was promoted to Lt. Colonel and remained in command of Ft. McHenry for the rest of his life. When he died in 1818, his widow Louisa began the custom of giving away pieces of the flag in honor of the memory of her husband and soldiers under his command. At her death in 1861, daughter Georgiana Armistead Appleton inherited the flag, and continued giving away cuttings. Georgiana bequeathed the flag to Eben Appleton who donated it to the Smithsonian Museum. By 1873 the flag was in pretty bad shape.

In 1914 the flag underwent a conservation process developed by Amelia Fowler that replaced the wool backing with Irish linen and secured the flag to the linen with 1.7 million stitches. The process also returned the flag to its original dimensions.

The more recent Star-Spangled Banner Preservation Project began in 1996. Conservators clipped Fowler’s 1.7 million stitches to remove the linen backing, used dry cosmetic sponges to lift debris from the flag, and brushed it with an acetone-water mixture to removes soils from the fibers. Staff then added a sheer polyester backing called Stabiltex to replace the linen. The restoration project concluded in 2008 with a total cost of $21 million.

Today the 206-year-old flag resides at National Museum of American History, part of the Smithsonian Institution, in a special pressurized chamber to protect it from light, humidity, and pollution.

*The 15-Star Flag represented the states of Connecticut, Delaware, Georgia, Kentucky, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Rhode Island, Vermont, Virginia.

NOTE: Americans often think the United States defeated Britain in the War of 1812, because Andrew Jackson’s troops were victorious at the Battle of New Orleans in January 1815. British and American representatives signed the Treaty of Ghent in December, 1814. The treaty restored boundaries to their pre-war lines. Congress ratified the treaty in February 1815.

Flag at Ft. McHenry by Lorax, 2003.

James Madison by Gilbert Stuart.

Francis Scott Key

Bombardment of Ft. McHenry, 1814.

Star-Spangled Banner Sheet Music

Ft. McHenry flag in 1873.

The large Star Spangled Banner before current restoration. Linen back attached in 1914 shows original length of flag.

Signing the Treaty of Ghent, 1814, by Amedee Forestier.

Christopher Klein. “9 things You May Not Know About “The Star Spangled Banner.” History. Sept. 12, 2014.

Cate Lineberry. “The Story Behind the Star Spangled Banner.” Smithsonian Magazine. Mar. 1, 2007.

Robert M. Poole. “Star-Spangled Banner Back on Display.” Smithsonian Magazine. Nov. 2008.

Sandra Wagner-Wright holds the doctoral degree in history and taught women’s and global history at the University of Hawai`i. Sandra travels for her research, most recently to Salem, Massachusetts, the setting of her new Salem Stories series. She also enjoys traveling for new experiences. Recent trips include Antarctica and a river cruise on the Rhine from Amsterdam to Basel.

Sandra particularly likes writing about strong women who make a difference. She lives in Hilo, Hawai`i with her family and writes a blog relating to history, travel, and the idiosyncrasies of life.