Next Sunday, March 17, is St. Patrick’s Day. You might wonder how a dour saint from fifth century Ireland could inspire our celebratory madness of green beer, parades, and dancing. And if such a man existed. The answer is . . . Well, let me tell you the stories first.

Next Sunday, March 17, is St. Patrick’s Day. You might wonder how a dour saint from fifth century Ireland could inspire our celebratory madness of green beer, parades, and dancing. And if such a man existed. The answer is . . . Well, let me tell you the stories first.

In the year 387 in Dumbarton, Scotland . . . Or Cumberland, England . . . Or Northern Wales a child named Maewyn Succat was born into a family as stable as any kin group could be in the fourth century. Which is to say, to a family subject to the whims of weather, cattle raiders, and eventually slave raiders. Maewyn Succat’s grandfather was a Christian priest; his father a community leader. When Maewyn Succat was about sixteen years old, Irish slave raiders captured him, along with a large number of his father’s vassals and slaves.

In Ireland Maewyn Succat’s master Milchu was a clan chief who sent the youth to watch the sheep. It was hard times for Maewyn Succat, but he made the best of it, learned the Irish language and social customs, and decided that he preferred his family’s Christian faith to that of the druids around him. In later years, Maewyn Succat remembered that he prayed daily “in the woods, and on the mountain, even before dawn.” And then he had a dream that if he could make it to the coast, he could escape Ireland. The dream came true; sailors smuggled Maewyn Succat onto their ship, and they sailed away to . . . France.

In Auxerre, France Maewyn Succat became a bishop and took a new name: Patricius, or Patrick, meaning father figure. Patrick had another dream. This time, “all the children of Ireland from their mothers’ wombs were stretching out their hands” to him. Patrick knew he must return to Ireland and convert the island to Christianity.

In Auxerre, France Maewyn Succat became a bishop and took a new name: Patricius, or Patrick, meaning father figure. Patrick had another dream. This time, “all the children of Ireland from their mothers’ wombs were stretching out their hands” to him. Patrick knew he must return to Ireland and convert the island to Christianity.

Patrick arrived back in Ireland, at Slane, on March 24, 433. He was 43 years old — which was a venerable age at the time. For the next forty years, Patrick converted people, built churches, and established monasteries.

Legend says Patrick had a walking stick made from ash wood, and that he planted it in the ground while he preached in an area. In one place it took Patrick so long to persuade the people to be baptized that when he was ready to leave, Patrick discovered his stick had taken root. I suspect he pulled it up just the same.

There are other stories. Patrick used the lowly shamrock to explain the Christian concept of Trinity to his listeners. Just as the shamrock has three leaves but is one, so God was Father, Son, and Spirit and yet one. I’m not sure what people concluded from that story, or even if it was important to them. But the shamrock was important to pre-Christian Irish and the number three was significant.

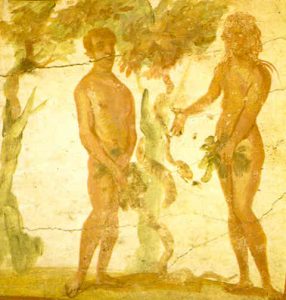

There is also the story that while Patrick was undergoing a 40-day fast, snakes attacked him. He was so angry he drove them into the sea, which is why there are no snakes in Ireland . . . Except there’s no evidence there ever were any snakes in Ireland. No doubt the term snake was a metaphor for the devil who tempted Adam and Eve to sin, implying Patrick drove the devil out of Ireland, and who can say he didn’t?

There is also the story that while Patrick was undergoing a 40-day fast, snakes attacked him. He was so angry he drove them into the sea, which is why there are no snakes in Ireland . . . Except there’s no evidence there ever were any snakes in Ireland. No doubt the term snake was a metaphor for the devil who tempted Adam and Eve to sin, implying Patrick drove the devil out of Ireland, and who can say he didn’t?

It turns out, that though Patrick’s day became a church feast day in the seventeenth century, Patrick was never actually canonized as a saint, but he became someone more important.

Patrick became a symbol for Ireland and the Irish Diaspora.

In 1737 the Charitable Irish Society of Boston held the first St. Patrick’s day parade. New York followed suit in 1762. And in 1798 St. Patrick became associated with the color green, because during the Irish Rebellion that year, Irish fighters wore green to contrast with British red, and popularized the song The Wearin’ o’ the Green.

O Paddy dear, and did ye hear the news that’s goin’ round?

The shamrock is by law forbid to grow on Irish ground!

No more Saint Patrick’s Day we’ll keep, his color can’t be seen

For there’s a cruel law ag’in the Wearin’ o’ the Green.”

I met with Napper Tandy, and he took me by the hand

And he said, “How’s poor old Ireland, and how does she stand?”

“She’s the most distressful country that ever yet was seen

For they’re hanging men and women there for the Wearin’ o’ the Green.”

“So if the color we must wear be England’s cruel red

Let it remind us of the blood that Irishmen have shed

And pull the shamrock from your hat, and throw it on the sod

But never fear, ’twill take root there, though underfoot ’tis trod.

When laws can stop the blades of grass from growin’ as they grow

And when the leaves in summer-time their color dare not show

Then I will change the color too I wear in my caubeen

But till that day, please God, I’ll stick to the Wearin’ o’ the Green.

Take a Listen

https://youtu.be/WsoeoEFwnUI

As Irish immigrants poured into America, Irish populations grew, and the St Patrick’s day customs took root.

- A feast of corned beef, cabbage, potatoes and other inexpensive foods

- Parades

- Drinking beer and whiskey

Today Americans rejoice with green beer, whiskey, Guinness, shamrocks, leprechaun hats and all manner of silliness. In 1962 Chicago began dying the Chicago River green.

Question: How does a sheep dog round up pub patrons for a glass of Guinness?

Answer Below

☘️☘️☘️

St. Patrick Window. St. Patrick Catholic Church, Junction City, OH. By Nheyob.

Adam and Eve with the Snake in the Roman catacombs. Public Domain.

St. Patrick Greeting. Public Domain.

Green Chicago River, 2009. By Mike Boehmer.

St. Patrick. Catholic Online.

Saint Patrick. Franciscan Media.

The Wearing of the Green. Ireland-information.

Ashley Ross. “The True History Behind St Patrick’s Day.” Time. March 8, 2019.

Sandra Wagner-Wright holds the doctoral degree in history and taught women’s and global history at the University of Hawai`i. Sandra travels for her research, most recently to Salem, Massachusetts, the setting of her new Salem Stories series. She also enjoys traveling for new experiences. Recent trips include Antarctica and a river cruise on the Rhine from Amsterdam to Basel.

Sandra particularly likes writing about strong women who make a difference. She lives in Hilo, Hawai`i with her family and writes a blog relating to history, travel, and the idiosyncrasies of life.