When I was young, I enjoyed visiting “historic” houses. At that time, I equated “historic” with an 18th or 19th century house. A house that was simply “old” didn’t impress me much, because a house from 1930 didn’t strike me as being all that different from a house of 1960. But a house from 1830 . . . that was something I found interesting. Such a house did not exist in the West Coast suburbs where I grew up.

Later, I realized that living in a house built in 1830 was much more labor intensive than a space where I actually wanted to live. Such a house had not come with indoor plumbing or heat. The windows weren’t glazed to keep out the cold, and the washing “machine” was a wooden tub with a wringer.

And yet . . . I’m still attracted to historic houses.

Visiting Rowley, on Boston’s North Shore, was nothing short of a cornucopia of historic houses. Large ones and small, they housed the villagers. The exteriors are strictly regulated by the Rowley Historic District Guidelines, but interiors are modernized.

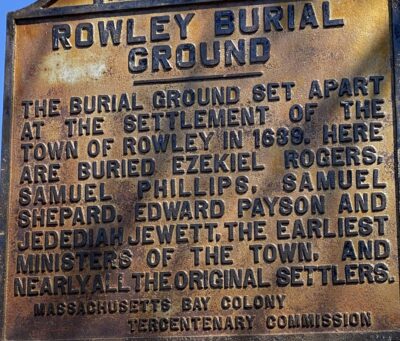

On Main Street, I passed several of these houses as I walked from my accommodation at the Briar Barn Inn to the Three Sweet Peas Bakery for breakfast. I also passed the Town Common, once known as the Training Place, and the Rowley Burial Ground, established in 1639 when Rowley was founded.

The Town Common, laid out by the first settlers, was once used for training by the local militia. In 1775, Benedict Arnold’s troops camped in the open space on their way to invade Quebec. Today, children’s sports teams hold practices on the grass. A pleasant gazebo provides a focal point, and at the opposite end, there is a statue in tribute of Rowley men who served in the American Civil War.

The Burial Ground contains the remains of nearly all the original settlers to Rowley. Two men who accused Margaret Scott of witchcraft are buried here.

The Burial Ground is well maintained with the oldest grave markers closest to the front. Some stand tall and proud; others are almost obscured by loose soil and leaves. I’ve walked through burial grounds before, but this time my stroll felt different, because the grounds are surrounded by buildings almost as old as the earliest markers. The extensive grounds are still in use.

But, back to the houses

As mentioned above, my unscientific research occurred as I walked from the Briar Barn Inn to the Three Sweet Peas Bakery. The house on the left is located at 142 Main Street

A corresponding photograph on the Historic Massachusetts, website identifies the structure as the Thomas Lambert House first constructed about 1699 by Thomas Lambert Jr for his bride. In 1977, the Lambert family sold the house. It appears that the rooms on the right hand side were original, but the date of construction for the left hand rooms is unclear. A real estate site values the 3-bedroom 2.5 bath house at $855,400

In contrast, the house at 157 Main Street built in 1834 with four bedrooms and 3.5 bathrooms is valued at $667,600.

The Cressey House at 15 Summer Street was built in 1750 but moved to its current location in 1810. The movers planned to place the house further back from the street, but the structure became stuck in the mud and still remains in the spot where the mud claimed it. The 5-bedroom, 30 bathroom property is value at $702,200. I think the two bay windows on either side of the front door are charming, as well as the only bay windows I observed.

In 1918 the barn on the property was converted into a house that sits next door.

Historic houses can be charming, and, up to a point, can be renovated by the owner. But before bidding on a piece of history, potential buyers should consult the Historic District Guidelines. Among the stipulations: exterior features such as cornices, brackets and window moldings should be retained. Outbuildings, such as a barn, may be put to other uses, but their exteriors should be kept in their original form. And, if you need to repair the chimney, keep in mind the bricks should match the size and colors of the originals. And, forget about vinyl siding. The exterior walls were built from wood, and that appearance must be maintained. This picture of the First Baptist Church built tin 1830 gives a good idea of exterior maintenance challenges. Do the words scrape and paint resound with you?

Owning an historic house is far different from admiring it. Besides the multitude of problems associated with old fixtures and wooden exterior walls, the legal definitions and Historic District rules impact even the most seemingly straightforward modifications.

The Town of Rowley vs. Michael K. Kovalchuk

An obscure, but dramatic, legal case illustrates the type of dispute that can arise in a designated historic district. Mr. Kovalchuk owned an 18th century house at 238 Main Street before the property fell into the Rowley’s new Historic District in 1985.

In addition to the 18th century house, Mr. Kovalchuk owned the 6.8 acres surrounding it. In 2017, Kovalchuk erected a 6-foot stockade fence without permission from the Historic District Commission.

The Commission filed a complaint, asserting that the house was one of two in Rowley with a gambrel-type roof, which increased its historic value. And, not only did the new fence block public view of the house, it clashed with the white picket fence next door. [A gambrel roof features a steeper lower slope with a less steep upper slope on each of the two sides.]

Mr. Kovalchuk responded that he had a firewood business on the property and the fencing was to protect the community, particularly children who might decide to play on potentially dangerous equipment. In addition, he had an agreement with the Board of Selectmen that predated the Historic District. The agreement, he said, allowed him to build the fence to protect the public from hazards associated with his business.

The Town of Rowley disagreed, and in August 2017, demanded that Mr. Kovalchuk remove the fence and fined him $100 a day until he did so, plus legal fees and court costs. Mr. Kovalchuk responded by putting his property up for sale with a $2.4 million asking price, because the property was in a prime location for development. The house is still listed in Mr. Kolvachuk’s name. Zillow presently values Kovalchuk’s two-bedroom, 1.5 bath house at $540,100. [You can check out a picture of the property at the Zillow site.]

Someone tore down the controversial fence before the court ordered deadline, but that was not the last word on the controversy. In ongoing litigation, Mr. Kolvachuk asserted he had engaged in forest activity since 1976, that in 1981 he purchased 2.4 acres at 238 Main Street and notified the Zoning Board that he planned to sell lumber and firewood. The Board ruled he did not need a license for his business, and that he could use a chainsaw as needed.

Four years later, Rowley changed zoning in the Central District, but allowed pre-existing businesses to continue. Ten years after that, Kolvachuk applied for a permit to build a second barn for storage related to his business. The Board ruled against him, and noted that his business didn’t meet criteria for agricultural use, because it occupied less than 5 acres. Kolvachuk didn’t build the barn, but purchased additional land to bring his holding up to 6.8 acres, and operated an un-permitted sawmill. Eventually, the case reached Superior Court which ruled that while Mr. Kolvachuk could operate his business, he could not use a saw mill. The decision was upheld on appeal.

And here the saga of 238 Main Street ends. The fence is gone, as is the business. And the historic houses keep watch from their positions throughout Rowley.

🏡 🏡 🏡

Alternate Version of official Rowley logo by Rowley 375 Committee.

Photos by Author.

Real Estate Valuations Taken from Zillow.com

The Ancient Houses of Rowley, Mass., Historical Massachusetts.

Rowley Historic District Guidelines.

Dave Rogers. “Homeowner Embroiled in Lawsuit Puts Property Up For Sale.” The Daily News. Aug. 2, 2017.

Dave Rogers. “Rowley Historic House Owner Removes Illegal Fence.” The Daily News. Oct. 3, 2017.

Inhabitants of the Town of Rowley v. Kovalchuk. Essex ss Superior Court. Massachusetts Lawyers Weekly.

Town of Rowley vs. Michael K. Kolvachuk. May 10, 2001.

Sandra Wagner-Wright holds the doctoral degree in history and taught women’s and global history at the University of Hawai`i. Sandra travels for her research, most recently to Salem, Massachusetts, the setting of her new Salem Stories series. She also enjoys traveling for new experiences. Recent trips include Antarctica and a river cruise on the Rhine from Amsterdam to Basel.

Sandra particularly likes writing about strong women who make a difference. She lives in Hilo, Hawai`i with her family and writes a blog relating to history, travel, and the idiosyncrasies of life.