This is a story about Lillian Gilbreth and how she applied principles of scientific management developed by Frederick Taylor to modernize American kitchens.

Taylor believed there was one best way to accomplish any task. The trick is to find it. Once the method is discovered, tools and work methods can be standardized to increase efficient production.

Enter Frank Gilbreth who noticed bricklayers wasted time when they bent over to pick up each brick, rather than reaching to a nearby table. By moving the brick supply, Frank increased the rate of bricklaying from 1,000 a day to 2,700 a day.

Frank discovered other ways to save time. Surgeons, for example, wasted time when they retrieved their own instruments during an operation. Frank suggested surgical nurses could pass the doctor instruments when they were needed.

Lillian Moller Gilbreth

Lillian met Frank in 1903 when she passed through Boston on her way to Europe. The couple married in 1904. For the next twenty years, Lillian gave birth to a child approximately every fifteen months, culminating in thirteen births and eleven surviving children. She also co-founded a consulting firm with her husband.

In 1912, the family moved to Rhode Island to apply scientific management principles to the New England Butt Company in the production of cast iron butt hinges. While there, Lillian earned a PhD in Psychology (1915).

Lillian contributed equally to her husband’s work, but her name was either left of their publications, or listed without showing her given name. If asked, Frank said the co-author was a family member. Busy with her family and professional life, Lillian wasn’t concerned about receiving publication credits. In order to combine work and family life, the Gilbreths worked out of their home and adapted domestic life to accommodate professional concerns.

Lillian later wrote that “we considered our time too valuable to be devoted to actual labor in the home. We were executives. So we worked out a plan for the running of our house, adopting charts and a maintenance and follow up system as is used in factories.” * Chores were standardized with a bidding system for larger jobs.

In 1924, Frank died of a heart attack. Lillian continued the consulting business, but it didn’t pay the bills because clients didn’t think she was professionally qualified. Out of necessity, Lillian began thinking of ways she could link her expertise to the changing needs of middle class women.

Lillian had three unique qualifications: practical experience with industrial engineering; a doctorate in psychology; and a household consisting of eleven children, a fact that made her recommendations carry domestic authority. During the 1920s urban households changed. Most homes had hot and cold running water, electricity, and appliances. But domestic workers were in short supply. Here was a niche Lillian could fill by maximizing household efficiency.

In 1926, Lillian began time and motion studies to determine the best way to make a bed, set a table, and wash dishes. She concluded that it was possible for a woman to reduce the walking distance covered during the process of washing dishes and putting them away from 26 miles per year to 6, and this meant a time savings as well.

Lillian told women they could measure their own needless walking with a pin and string method. A child follows the home-maker around with a ball of string and leaves a trail that records the distance walked. A series of pins note where turns take place. With this information, a woman could arrange her tasks more efficiently, and with the time saved, she could participate in other activities.

In 1927 Lillian published The Home-Maker and Her Job. Drawing on her background in industrial engineering, Lillian advised wives to decide exactly what tasks needed to be done and whether they could be done more efficiently.

In particular, Lillian looked at the kitchen, a work space consuming half or more of a home-maker’s time. Lillian didn’t know how to cook, but she could perform a time and motion study on baking a cake.

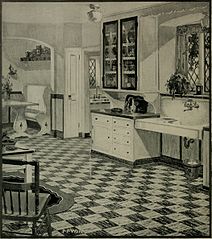

In 1927, kitchens generally followed a design called a ‘loose kitchen.’ This was a large room, with furnishings including a table, a free-standing cupboard, an ice box, a sink with a drying board, and a stove. Cooking ingredients and cookware could be across the room from the counter, or in separate pantry area.

Lillian developed what she called a ‘circular routing‘ kitchen, to reduce steps. She put the stove and counter side-by-side, with food storage above the counter top and pan storage below. The refrigerator was a step away. A rolling cart provided more surface area where it was needed. This basic design is still in use.

Lillian partnered with the Brooklyn Borough Gas Company to develop a Kitchen Practical using gas appliances. Lillian also introduced the concept of adding interior shelves to refrigerator doors, the foot-pedal trash can, and wall light-switches to replace the central light fixture turned on by pulling a chain.

“When you go to your man-designed kitchen in the dark and fan the air wildly as you hunt vainly for the chain to pull the electric light on, only to have it eventually hit you in the face, you have a simple enough problem in the elimination of unnecessary fatigue in the household. Get rid of the waste motion by having a push button at a convenient place on the wall.”**

It seems such an obvious solution . . . once someone thinks of it.

🍳🍳🍳

*Quoted in Laurel D Graham. “Domesticating Efficiency: Gillan Gilbreth’s Scientific Management of Homemakers, 1924-1930.” Signs. Vol 24. No. 3. 1999. pp 633-675.

**Ibid.

Illustrations

Lillian Moller Gilbreth.

Bricklayer on construction site in Belgium by Jamain.

Homework. FOTO:FORTEPAN / Lencse Zoltán.

The Modern Home Pamphlet.

1930s kitchen with resilient squares of US Rubber Tile.

Youngstown Kitchen by Mullins 1948.

Double Toggle Light Switch by Freekhou5.

“Lillian Gilbreth, Genius in the Art of Living.” New England Historical Society.

Laurel D Graham. “Domesticating Efficiency: Gillan Gilbreth’s Scientific Management of Homemakers, 1924-1930.” Signs. Vol 24. No. 3. 1999. pp 633-675.

Alexandra Lange. “The Woman Who Invented the Kitchen.” Slate. Oct 25, 2012.

Sandra Wagner-Wright holds the doctoral degree in history and taught women’s and global history at the University of Hawai`i. Sandra travels for her research, most recently to Salem, Massachusetts, the setting of her new Salem Stories series. She also enjoys traveling for new experiences. Recent trips include Antarctica and a river cruise on the Rhine from Amsterdam to Basel.

Sandra particularly likes writing about strong women who make a difference. She lives in Hilo, Hawai`i with her family and writes a blog relating to history, travel, and the idiosyncrasies of life.