You may not have noticed, but we have an extra day this month. Leap Day, February 29, is this Saturday. For most of us, it’s just another day, but it’s existence is what keeps our solar calendar in sync with the earth’s orbit around the sun. So let’s do some calendrical history.

The Ancient Romans used a lunar, rather than a solar, calendar. Lunar months are about 29.5 days long, with years of only 354 days. Without adjustments, the Roman calendar failed to mesh with the seasons.

Contemporary Egyptians, on the other hand, used a calendar that divided the year into 12 months with 30 days each. At the end, they added five days of festivals, both for enjoyment and to keep the calendar in tune with the seasons.

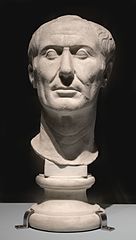

By the time Julius Caesar met Cleopatra in 48 BCE, the Roman lunar calendar had diverged from natural seasons by about three months. By then, the Egyptians had developed a 365 day year with a leap year every four years.

Two years later, Caesar issued a new calendar known as the Julian calendar. The Julian calendar declared a year to be 365.25 days, with a leap day every fourth year to keep the calendar in tune with the seasons. In order to shift to the new calendar, Caesar ordered a single 445 day long Year of Confusion to correct the drift, and then enacted the new calendar.

That worked for over 100 years, but there was a discrepancy. The Julian calendar called for a technical year of 365.25 days, but the actual extra time was 365.242 which meant that the calendar year was 11 minutes shorter than the solar year. Which isn’t much, but after 128 years the solar calendar and the Julian calendar diverged by an entire day.

This wasn’t initially noticeable. But by the 16th century the drift reached a point where important days, like Christmas, had moved about 10 days. Tsk. Tsk.

Pope Gregory XIII decided to get Christmas back where it was supposed to be, and instituted a revised Gregorian calendar in 1582. This one has leap years every four years, except when a year is evenly divisible by 100, but not by 400. For example, the year 1900 would have been a leap year, but 1900 / 100 = 19. By comparison, 2020 / 100 = 20.2 so we’ll go ahead with Leap Year on Saturday.

Leap Day Dilemmas

Leap Days bring up interesting situations. For example, if you’re born on February 29, when do you celebrate your birthday? Either February 28 or March 1. But . . .

Gilbert and Sullivan’s Pirates of Penzance is built around a character named Frederick. Frederick’s family inadvertently apprenticed him to a group of pirates until his 21st birthday. But, when the day arrives, he finds out he was actually born in February 29, so though he’s reached his 21st year, he won’t be officially 21 for another 63 years. Thus the musical launches its improbably silliness.

In the past, Leap Day was also an occasion of unusual marriage proposals. An Irish tradition says that St. Bridget asked St. Patrick to allow women to propose marriage to their suitors, because some men were too timid to propose. St. Patrick didn’t like the idea, but said women could make a proposal on Leap Day. Legend has it that St. Bridget immediately proposed to St. Patrick who declined, but kissed her on the cheek and gave her a silk gown.

The custom grew that women could propose marriage on Leap Day, and if the man refused, he must give her a silk gown, or, in some cases, 12 pairs of gloves so she can hide the embarrassment of a hand without a wedding ring.

That custom, needless to say, has fallen out of use.

🧤🧤🧤

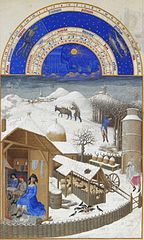

February from Tres Riches Heures du duc de Berry 15th century.

Cleopatra

Julius Caesar. Photo by Angel M. Felicisimo. Bust may be the only surviving bust made during Caesar’s lifetime.

Sun and planets by WP

St. Bridget and St. Patrick windows at St. Peter’s Church, Yorks by Jules & Jenny

Evan Andrews. “Why do we have leap year?” History. Aug 22, 2018.

Brian Handwerk. “The Surprising History Behind Leap Year.” National Geographic. Feb. 26, 2014.

Sandra Wagner-Wright holds the doctoral degree in history and taught women’s and global history at the University of Hawai`i. Sandra travels for her research, most recently to Salem, Massachusetts, the setting of her new Salem Stories series. She also enjoys traveling for new experiences. Recent trips include Antarctica and a river cruise on the Rhine from Amsterdam to Basel.

Sandra particularly likes writing about strong women who make a difference. She lives in Hilo, Hawai`i with her family and writes a blog relating to history, travel, and the idiosyncrasies of life.