This Friday is St. Patrick’s Day. There will be quantities of green beer, lots of people wearing green, parades, consumption of corned beef & cabbage, and festivities for young and old. The day is so much a part of American culture that it’s easy to forget the Irish were once unwanted immigrants.

Between 1820 and 1930 about 4.5 million Irish emigrated to the United States. To break down the figure further, it’s worth noting that in the 1840s the Irish constituted almost half of all immigrants entering America. American-born citizens disapproved of the Irish, because they were Catholic and an alleged menace to the American economic, political and social structure. In 1850 the population of native and foreign born in Boston divided at 50 per cent of each. Americans felt overwhelmed.

Observers noted that a disproportionate number of immigrants were thrown upon the public purse, and viewed them as lazy and indolent. They also charged immigrants were immoral, and always ready to brawl in the streets. “Who are the political, street, canal and railroad rioters? Foreigners! Men always ready and prepared to enter into any fray, whose object may be to resist the authorities.”**

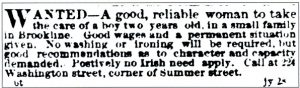

NO IRISH NEED APPLY

It was hard to find work. Many women and girls took positions as live-in domestics – when they could find them. This advert for a nanny describes a desirable position. The nanny would care for one child, aged two. No washing or ironing required, but “positively no Irish need apply.”

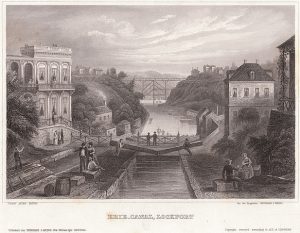

BUILDING THE ERIE CANAL

Men worked predominately as unskilled labor, most notably in the construction of the Erie Canal connecting the Great Lakes with New York.. Construction began in 1817. Plans called for a canal 363 miles long. The canal boats, which would take up to 3.5 feet in draft, would be pulled by horses and mules along the tow path. The canal itself had to be four feet deep and seven feet wide.

Promoters expected to hire locally along the route. But the work was backbreaking, exhausting labor with pick axes and shovels. Many lives were lost due to explosives. The Irish needed work and took the jobs. Employers housed them in shanties, which convinced local citizens the workers must be morally deficient. Part of the workers’ wages was paid in whiskey, which proved the men were drunkards. The canal opened in 1825.

ST. PATRICK’S DAY PARADES

St. Patrick’s Day Parades became a way to celebrate Irish-American unity. The first parade took place in New York City in 1762, a celebration by Irish troops in the British army. By the end of the nineteenth century parades occurred in Boston, Chicago, New York, San Francisco, and Savannah (Georgia). The events were a public announcement that the Irish were numerous, successful, and were staying in their new country.

Today the St. Patrick’s Day Parade in New York City is the largest St. Patrick’s parade in the world. The shortest parade is held in the Irish village of Dripsey. It lasts for the 100 yards between village’s two pubs.

St. Patrick’s Day is a time of shamrocks and fun. It’s also a good time to remember America is built on the hopes and sweat of immigrants from all faiths and nations.

SLAINTÉ!

☘☘☘

Sign up for Sandra’s Newsletter and get “Out-Takes from Rama’s Labyrinth.”The newsletter comes out every Monday with a blog preview & any relevant book announcements. You can unsubscribe at any time. Your contact information won’t be given out. Sign up today for free “Out-Takes from Rama’s Labyrinth.”

Illustrations from Wikimedia Commons:

Shamrock by Paul Kocialkowski. Creative Commons Attribution.

Early Irish Immigrants. Public Domain.

1868 Advertisement for a Nanny. Public Domain.

Erie Canal at Lockport New York. C. 1855. Public Domain.

St. Patrick’s Day Parade, Fifth Avenue, New York City. 1907. No Known Copyright Restrictions.

**Quoted by Ray Allen Billington. The Protestant Crusade. Chicago: Quadrangle Paperbacks. 1964. Page 194.

Mike Cronin. “How America Invented St Patrick’s Day.” Time.com. Mar. 15, 2015.

Erik Loomis. “This Day in Labor History: Oct 26, 1825.” Lawyers, Guns, & Money. Oct. 26, 2013

Sandra Wagner-Wright holds the doctoral degree in history and taught women’s and global history at the University of Hawai`i. Sandra travels for her research, most recently to Salem, Massachusetts, the setting of her new Salem Stories series. She also enjoys traveling for new experiences. Recent trips include Antarctica and a river cruise on the Rhine from Amsterdam to Basel.

Sandra particularly likes writing about strong women who make a difference. She lives in Hilo, Hawai`i with her family and writes a blog relating to history, travel, and the idiosyncrasies of life.