Last Monday, June 15th, the Magna Carta was 800 years old. Yeah, I know. It’s not a date on the tip of your tongue. But, without the Magna Carta there wouldn’t have been a Declaration of Independence, and without the Declaration we wouldn’t celebrate the 4th of July. And without the 4th of July, we’d miss our summer fireworks. So, it’s worth taking a trip back in time to see what all the fuss is about.

Okay, what’s the Magna Carta? And where did it come from?

So glad you asked.

The colorful story leading up to Magna Carta features some of the most famous players in medieval England, because in medieval England the personal was entirely political. The movers and shakers in our story are Henry II, Eleanor of Acquitaine, their five rebellious sons (including John the Tyrant), and Robin Hood. Well, Robin Hood isn’t actually that important but he is well known.

Henry was an ambitious man. In 1152 he married Eleanor of Aquitaine, the greatest heiress in western Europe. She was a beautiful woman. More importantly, she controlled a great deal of land. In 1153, Henry made good his claim to the English throne and became king in 1154. Turned out he was good at his job. King Henry established the king’s justice and asserted the crown’s claim to rule over the claims of his knightly barons.

Henry’s marriage Eleanor was less than idyllic, though in the early years they produced eight children: five sons and three daughters. As the boys became men, they rebelled against their father, often with their mother’s support. Henry finally placed Eleanor under house arrest.

Relations between the barons and the ruling king began to deteriorate in an elaborate game of Whose got the Power?

When Henry died in 1189, his son Richard became king. Richard left England to join the French king on the Third Crusade, appointing his brother John to serve as regent. This turned out to be an unpopular choice, giving rise to Robin Hood’s career of allegedly robbing the rich to give to the poor.

Although John was not a pleasant regent, the troubles of England weren’t entirely his fault. King Richard managed to be captured and held for ransom twice, which nearly bankrupted England.

In 1199, John got to rule in his own right. He wasn’t a popular king. Indeed, after his death, Matthew Paris famously commented,“Foul as it is, hell itself is made fouler by the presence of King John.” Ouch!

Yet the epitaph wasn’t not without cause. When asked to mediate a dispute involving the engagement of Isabella of Angoulame to Hugh de Lusignan, John divorced his wife and married Isabella himself. This violated the knightly code of conduct. When the French king Philip II called on John to explain his actions, John declined the summons and went to war.

This was a bad choice. By 1206 John lost almost all the English holdings in France. (Normandy, Anjou, Maine and parts of Poitou) No doubt his mother was rolling in her grave. John wasn’t prepared to concede. He needed money to continue the war, so he squeezed the English as never before. Taxes went through the roof, and John began to charge for everything. You want to inherit your father’s land – pay up.

John also annoyed the pope. Pope Innocent III appointed Stephen Langton as Archbishop of Canterbury. John refused to accept the appointment. The pope excommunicated John and placed England under and Interdict, which meant no church functions, could take place in England – no baptisms, marriages, funerals. A pretty stiff penalty for everyone in England. And, John’s barons no longer had to obey him. This created a severe threat to John’s job as king. In 1212, John agreed to make England accountable to the pope. This gave John new leverage with the implication that if the barons defied him, God would punish them. This was a more serious threat in the thirteenth century than it would be today.

But John never recognized when it was time to make compromises. He continued to fight in France, trying to regain the lost territories. Under feudal law, John had the right to demand soldiers or gold. When the barons refused to comply, John attacked their castles. Not surprisingly, the barons began to think about taking matters into their own hands. Making a bad situation worse, John lost the war against France a second time and agreed to pay the French king a massive crime in exchange for a truce. John imposed more taxes and fines. By this time the barons had an extensive list of grievances against King John.

Specifically, and not necessarily in order of importance, King John had violated the feudal contract with his barons.

- He repudiated his first wife, Isabella of Gloucester, in 1200.

- He married Isabella of Angouleme who was betrothed to his vassal High of Lusignan. This offended King John’s lord, King Philip Augustus of France who confiscated his French holdings.

- He fought the French king and lost almost all English holdings in France

- He quarreled with Pope Innocent III.

- He launched a new unsuccessful war against France and demanded military service and funds to pay for the war.

- He imposed what the barons viewed as steep, arbitrary fines for alleged violations.

In 1215 the barons did the unthinkable. They rebelled against the king – and they won. Now what?

Next Week: King John capitulates with Magna Carta

Acknowledgements:

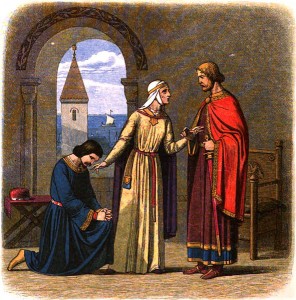

Featured Image: John and Barons. 1868. By Joseph Martin Kronheim. US Public Domain. Wikimedia Commons.

Sandra Wagner-Wright holds the doctoral degree in history and taught women’s and global history at the University of Hawai`i. Sandra travels for her research, most recently to Salem, Massachusetts, the setting of her new Salem Stories series. She also enjoys traveling for new experiences. Recent trips include Antarctica and a river cruise on the Rhine from Amsterdam to Basel.

Sandra particularly likes writing about strong women who make a difference. She lives in Hilo, Hawai`i with her family and writes a blog relating to history, travel, and the idiosyncrasies of life.

Bravo mini read!!! love it!