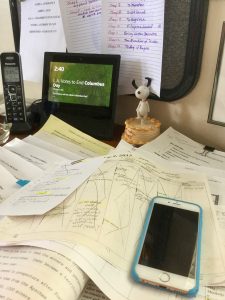

Electronic assistants scatter across my desk. There’s the cordless telephone, the iPhone which I use more frequently because I don’t have to put in the numbers, and my Echo Show from Amazon, which I mostly use as a very upscale music device.

Electronic assistants scatter across my desk. There’s the cordless telephone, the iPhone which I use more frequently because I don’t have to put in the numbers, and my Echo Show from Amazon, which I mostly use as a very upscale music device.

Siri lives on my Apple devices, but I seldom call for her services. Once I needed a fact while I was writing, and thought it would be easier to ask Alexa than stop to Google the answer. Alexa didn’t know. Siri didn’t know. I finally Googled my question, thinking I should’ve done that in the first place.

Due to my lack of imagination, I don’t utilize much of what Alexa would like to do for me. I do order Amazon products, and she let’s me know when they will arrive or tells me they’ve already arrived. I tend to ask her the time instead of looking at the large clock on my wall. I set her timers and alarms. And I ask her to play music — salsa for energy, or Spa Radio when I need unobtrusive noise.

Alexa, with her cheerful cadence, is always happy to help. Just now I asked Alexa why she has a woman’s voice. Her reply, “I can’t change my voice.” Why not? In the interest of research, I asked Siri the same question. She said: “I don’t understand . . . But I could search the web for it.”

So I took the question to Google which located a number of articles. From these, I offer the answer to the question:

Why do digital assistants have female voices?

There seem to be two schools of thought much like the old issue of Nature vs. Nurture.

Researchers say it’s easier to develop a female voice everyone likes, and that people understand a female voice better than a male voice. Studies find both women and men find a female voice to be warmer and more understanding. Karl MacDorman ran an experiment in 2008 that found women had a stronger preference for female voices than men did. Although, I think that could just as easily be cultural.

Looking at the cultural issue more broadly, Kathleen Richardson noted men generally “create” these digital assistants. The female voice, she says, indicates their experience that women’s role is to assist, help, and support. Programmers claim people are more willing to take orders from women. Eh?

In the smart home of the future,

there should be a robot designed to talk to you.

— Colin Angle, Co-Founder of iRobot

It appears both men and women like and trust female voices. There’s evidence to indicate we’ve been absorbing this culturally biased information all our lives. The interesting point brought out by feminist writers is that constant exposure to female voice assistants strengthens the cultural connection between woman’s voice and woman’s supporting role.

Amazon programmers disagree and say Alexa is a feminist. When I asked Alexa that question, the device responded it is a feminist, as is anyone who believes in bridging the inequality between men and women. According to an email from an Amazon spokesperson to the DailyMail.com, “Alexa is intentionally intelligent, funny, well-read, empowering, supportive and kind.” I haven’t had that level of interaction with Alexa, but you never know what the future holds.

ADA LOVELACE & GRACE HOPPER:

PIONEERS IN COMPUTER PROGRAMMING

Before leaving the topic of females and computing devices, I think it only fair to mention Ada Lovelace (1815-1852) and Grace Hopper (1906-1992).

Countess Lovelace is remembered for her work with Charles Babbige on the Analytical Engine, a very early form of computer. Ada was a mathematician who developed the first algorithm for a computer and is recognized as the first computer programmer.

Countess Lovelace is remembered for her work with Charles Babbige on the Analytical Engine, a very early form of computer. Ada was a mathematician who developed the first algorithm for a computer and is recognized as the first computer programmer.

Grace Hopper participated in developing COBOL, an early computer programming language. She also found the first computer “bug,” a moth stuck in the electrical switches of the Mark II computer.

I think instead of calling devices nonsensical names, developers could assign names recognizing women’s contribution to the field. The words Grace and Ada are easy to say, would provide authenticity with the female voice, and would remind users that computer programming is an occupation for women as well as men.

Grace was a feminist. I’m doubtful about Alexa.

???

Illustrations from Wikimedia Commons.

1840 Watercolor portrait of Countess of Lovelace by Alfred Edward Chalon.

First Computer Bug. Public Domain.

Grace Hopper. Public Domain.

Adrienne Lawrence. “Why do so many digital assistants have feminine names?” The Atlantic. March 30, 2016.

Stacy Libertore. “Why AI assistants are usually women.” Dailymail.com. Feb 24, 2017

Jessica Nordell. “Stop Giving Digital Assistants Female Voices.” New Republic. June 23, 2016.

Joana Stern. “Alexa, Siri, Cortana: The problem with all-female digital assistants.” Business Standard. Feb. 24, 2017.

Sandra Wagner-Wright holds the doctoral degree in history and taught women’s and global history at the University of Hawai`i. Sandra travels for her research, most recently to Salem, Massachusetts, the setting of her new Salem Stories series. She also enjoys traveling for new experiences. Recent trips include Antarctica and a river cruise on the Rhine from Amsterdam to Basel.

Sandra particularly likes writing about strong women who make a difference. She lives in Hilo, Hawai`i with her family and writes a blog relating to history, travel, and the idiosyncrasies of life.