It was a beautiful day in Augrangabad, India. The early morning was pleasantly warm. At mid-morning we neared the day’s temperature of 40∘ Centegrade – which is roughly 110∘ Fahrenheit for those of us who have yet to switch to metric. Either way, it was very warm. But, as the saying goes: “At least it was a dry heat.” In short, perfect conditions for an excursion to the Ajanta Caves which were two hours, 64 miles, and hundreds of years away.

This is the view from the lookout point. If you look straight down you will see the Waghora River bed. I don’t say river, since, at the time, there was no visible water. On the other hand, once the monsoons start, it fills up fairly quickly.

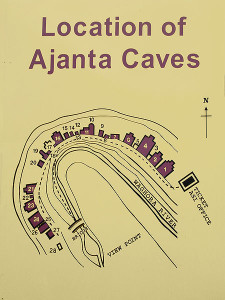

You can clearly see the 30 caves Buddhist monks hand-carved out of the cliff face. I wonder if they were meditating as they excavated – it would seem appropriate. Originally, the caves were accessed by individual ladders connecting to the riverside between 35 and 110 feet below.

We decided it would be fun to walk down from the look out. This is how I looked at the start. I had a hat, sturdy walking boots, and a ridiculous smile as I sat under the leafless tree. I’m sure I said something like “Sure, let’s walk down. Gravity is our friend.”

And here I am when we finally got to the first actual cave entrance. Note the glazed eyes and red face. And that’s before we actually started looking at the caves. The walk, by the way, was terrific.

But enough about me. Let’s talk about the Ajanta Caves – named as a UNESCO Heritage Site in 1983.

There were two phases of construction. Monks carved the first caves about the second century BCE, during the time Hinayana Buddhism was dominant. The second phase of excavation happened between the fifth and seventh centuries CE. By then, Mahayana Buddhism dominated and secular merchants provided both funding and supplies.

About the 8th century CE, the monks left, and the jungle returned. The caves slept peacefully until April 28, 1819 when John Smith, a British cavalry officer, bumped into them. I’ve seen conflicting accounts about what John was doing when he found the caves. One says he was hunting for tigers. Another said John was separated from his party after a tiger attacked them. I suppose both views are valid.

Basically, John was hanging out trying to decide what to do, when he noticed a rock wall covered by a thicket of vegetation. Of course, he had to check it out. And he discovered the wall was actually the edge of a horseshoe shaped window. We know this site as Cave No. 10. John was so impressed; he carved his name and the date on the wall. Of course, that was the very top of the wall, so the carving is barely visible now. It is probably safe to say, John did not know the value of his discovery, but he did report it to the Nizam of Hyderabad.

The 30 caves are arranged in a horseshoe pattern that follows the curve of the Waghora River below.

So what do the caves look like? Now that I have caught my breath, you see me outside Cave No. 19, completed about 600 CE.

This is from the later period of cave construction. The monks wanted to get away from the world, so they carved individual cells inside. So, how does that look? Kind of dark, if you discount the artificial lighting.

And the individual cell? It may not be a bed of nails, but a rock bed indicates a somewhat austere lifestyle.

Ajanta Caves are particularly known for their wall and ceiling paintings. This painting is a palace scene from a story about Buddha.

The colors remain amazingly vibrant. More than the elements, I was told the biggest threat to their survival was the use of an alcohol solvent in an effort to clean them. Oops.

The paintings are a type of tempura. First the monks evened out the rock surface with a mixture of clay, cow dung and rice husks. Then, they applied a coat of lime to create the polished surface on which the artist used a fresco technique, applying the paint onto a wet surface.

The image below is from Cave No. 2 called the “Epiphany of Buddha.” Done in 60 CE, it reflects Mahayana iconography showing various aspects of Buddha.

The earliest monks did not depict images of Buddha, but instead indicated his presence by a stupa, as in Cave 26. The ceiling arches look like wood, but are actually stone.

Visiting the Ajanta Caves was an incredible privilege. Walking down the mountain in the heat allowed me to imagine the type of isolation the monks must have experienced – although they were not completely off the trade route pathway. Experiencing manmade caves of such magnitude – it took generations to create the caves, and even longer to decorate them with sculpture and painting – reminded me that time is, in fact, endless. The devotion, commitment, and determination of these anonymous monks is a dramatic contrast to our modern lives of technology and instant gratification.

For a day, I glimpsed a timeless realm.

Unless otherwise noted, all photos by Author. All Rights Reserved.

For more information on the Ajanta Cave, check out:

http://www.kamit.jp/02_unesco/02_ajanta/aja_eng.htm

http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/242/

Sandra Wagner-Wright holds the doctoral degree in history and taught women’s and global history at the University of Hawai`i. Sandra travels for her research, most recently to Salem, Massachusetts, the setting of her new Salem Stories series. She also enjoys traveling for new experiences. Recent trips include Antarctica and a river cruise on the Rhine from Amsterdam to Basel.

Sandra particularly likes writing about strong women who make a difference. She lives in Hilo, Hawai`i with her family and writes a blog relating to history, travel, and the idiosyncrasies of life.