“We will open the book,” wrote the poet Edith Lovejoy Pierce. “The pages are blank. We are going to put words on them ourselves. The book is called opportunity, and its first chapter is New Year’s Day.”

“We will open the book,” wrote the poet Edith Lovejoy Pierce. “The pages are blank. We are going to put words on them ourselves. The book is called opportunity, and its first chapter is New Year’s Day.”

Do you have a blank journal where you jot down musings, observations, or reminders? Many of us possess such a journal, often purchased from a display near the cashier at a bookstore. So enticing with their smooth covers and ribboned page markers.

No bookstore nearby? Sometimes journals arrive as gifts. Either way, most often they sit on a shelf. Because, after all, who has time to write down random thoughts?

I don’t know when Ms. Pierce wrote the chapter called New Year’s Day. She died in 1983, before our lives were taken over by keyboards. Let’s take a moment to consider what she might have written on the first day of her Book of Opportunity. Do you think it was something as banal as a New Year Resolution?

A Resolution on New Year’s Day, or any other day, is simply a decision to do something, or not to do something. Secondarily, this decision may solve a problem or provide an answer.

That’s it.

In our culture, a New Year Resolution is nothing so much as a promise to yourself. You might keep it; you might not. Two years ago I “resolved” to get my digital photos into printed albums. It was an open-ended promise, because there was no deadline. I finished last month.

Western culture’s approach to the new year is rooted in Roman customs. When Rome was a Republic, new year celebrations took place near the Spring Equinox. Public ceremonies demanded the presence of all government officials and generals. As Rome acquired territory, the generals had a problem. Military campaigns took place in the spring, but couldn’t begin until ranking military officers returned from Rome.

About 300 BCE Romans shifted the start of the year to January, in honor of the two-headed god Janus, ruler of change and new beginnings. Conveniently possessed with two heads, Janus could look back to the old year and ahead to the new. Public ceremonies occurred in the morning. The afternoons were for more personal celebrations. People gave each other honey and pears and wished friends and family a sweet new year.

About 300 BCE Romans shifted the start of the year to January, in honor of the two-headed god Janus, ruler of change and new beginnings. Conveniently possessed with two heads, Janus could look back to the old year and ahead to the new. Public ceremonies occurred in the morning. The afternoons were for more personal celebrations. People gave each other honey and pears and wished friends and family a sweet new year.

During the Late Roman Empire, Christians began erasing pagan customs in favor of church observances. As the Middle Ages unfolded, the Church encouraged prayer vigils and confessions. Very grim, not to mention cold. The Church insisted the beginning of a new year was a perfect time to repent, beg forgiveness, and promise to do better. But try as it might, the Church was unable to persuade knights and lords to forgo their pleasures.

The VOW OF THE PEACOCK possibly evolved as an alternative to repentance. Medieval knights admired peacocks. They thought the splendor and colors of male plumage equalled the kings’ majesty. The knights also thought peacock flesh was the diet of valiant knights.

The VOW OF THE PEACOCK possibly evolved as an alternative to repentance. Medieval knights admired peacocks. They thought the splendor and colors of male plumage equalled the kings’ majesty. The knights also thought peacock flesh was the diet of valiant knights.

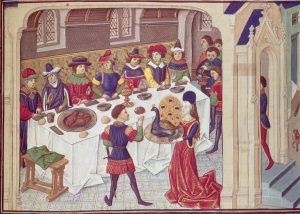

During the last feast of Christmas which probably occurred on January 5, ladies escorted a peacock into the hall. The peacock might be alive, but was usually roasted. It arrived with full plumage intact. Each knight placed his hand on the peacock and made a vow to renew his commitment to the rules and life of chivalry. The bird was then carved and portions given to each knight.

During the last feast of Christmas which probably occurred on January 5, ladies escorted a peacock into the hall. The peacock might be alive, but was usually roasted. It arrived with full plumage intact. Each knight placed his hand on the peacock and made a vow to renew his commitment to the rules and life of chivalry. The bird was then carved and portions given to each knight.

None of these early promises were called resolutions. The phrase didn’t appear until 1813 when a Boston newspaper used it. Puritans, the founders of Boston, used birthdays and the new year as a time when people should ponder their shortcomings and commit to better behavior. I’m guessing this is where our modern connotation of a new year resolution comes from. The Puritans conscientiously entered their faults and new resolve into their journals. They may have been more serious about the exercise than we are. If they failed, they went to hell, or so they thought.

Ms. Pierce was a twentieth century woman unlikely to be concerned with hellfire. She merely observed that each year our journal, like our calendar, is fresh and new – even if it’s a digital calendar. We write upon it what we will. And if we don’t share what we write, no one will ever know if we succeed or not.

???

Illustrations from Wikimedia Commons.

Young Woman Reading A Book by Renoir. Public Domain.

Janus Statue. Vatican Museum. Public Domain.

Male Peacock by Alex Pronove. Creative Commons Attribution.

Roasted Peacock. From Vows of the Peacock. 15th Century. Public domain

A. L. “The Origin of New Year’s Resolutions.” The Economist. Jan. 5, 2018.

Evan Andrews. “5 Ancient New Year’s Celebrations.” History. Dec. 31, 2012.

Shanna Hehlen. “Why do we make New Year’s Resolutions?” Mental Floss. Dec. 31, 2017.

Katy Waldman. “Bring Back the Peacock Vow.” Slate. Jan. 3, 2014.

Sandra Wagner-Wright holds the doctoral degree in history and taught women’s and global history at the University of Hawai`i. Sandra travels for her research, most recently to Salem, Massachusetts, the setting of her new Salem Stories series. She also enjoys traveling for new experiences. Recent trips include Antarctica and a river cruise on the Rhine from Amsterdam to Basel.

Sandra particularly likes writing about strong women who make a difference. She lives in Hilo, Hawai`i with her family and writes a blog relating to history, travel, and the idiosyncrasies of life.